The Atsina people were much smaller in number than the surrounding Cree nation and found themselves at loggerheads with the much better-armed and mighty group. Due to this, Atsina warriors relied on stealth more than direct conflict when dealing with attacks.

Dutch and French traders were supplying the Cree and Assiniboines with guns in a trade agreement as the fur industry grew. The far less powerful bow and arrow were no match for the bullets from the Cree, who were driving the Atsina out of their homelands to hunt. In retaliation, the Atsina burnt down two trading posts.

Ready for War

A procession of Atsina warriors, in full battle regalia, head to battle in this astonishing photograph taken by Edward S. Curtis. The Atsina, known to Europeans as “Gros Ventres,” were formidable fighters and often engaged in skirmishes. One of the most well-documented battles, the Battle of Pierre’s Hole, involved the Gros Ventre holding ground against several American trappers and numerous Iroquois tribespeople.

The battle concluded with twenty-six Gros Ventre fatalities for the twelve deaths of their foes. At the end of the battle, a soldier wrote, “‘The din of arms was now changed into the noise of the vulture and the howling of masterless dogs.”

Cheyenne Animal Dance

A large gathering of Cheyenne people splashes their faces with water during a ceremonial dance known as “the animal dance.” Animal dances were prevalent throughout the ancient Native American cultures, and some still remain. They are deeply rooted in Native American cultures and defied strict patterns, mirroring the fauna within each tribe's vicinity. First Nation communities celebrated with bear dances, while the Pueblo people honored the mule deer through dynamic dance rituals.

These captivating performances represented a sacred connection to nature, embodying the spirit and essence of the animal kingdom. Through rhythmic movements, detailed costumes, and spirited chants, these dances resonated with the collective identity and reverence for the animal world, embracing a harmonious relationship between humans and the creatures that shared their ancestral lands.

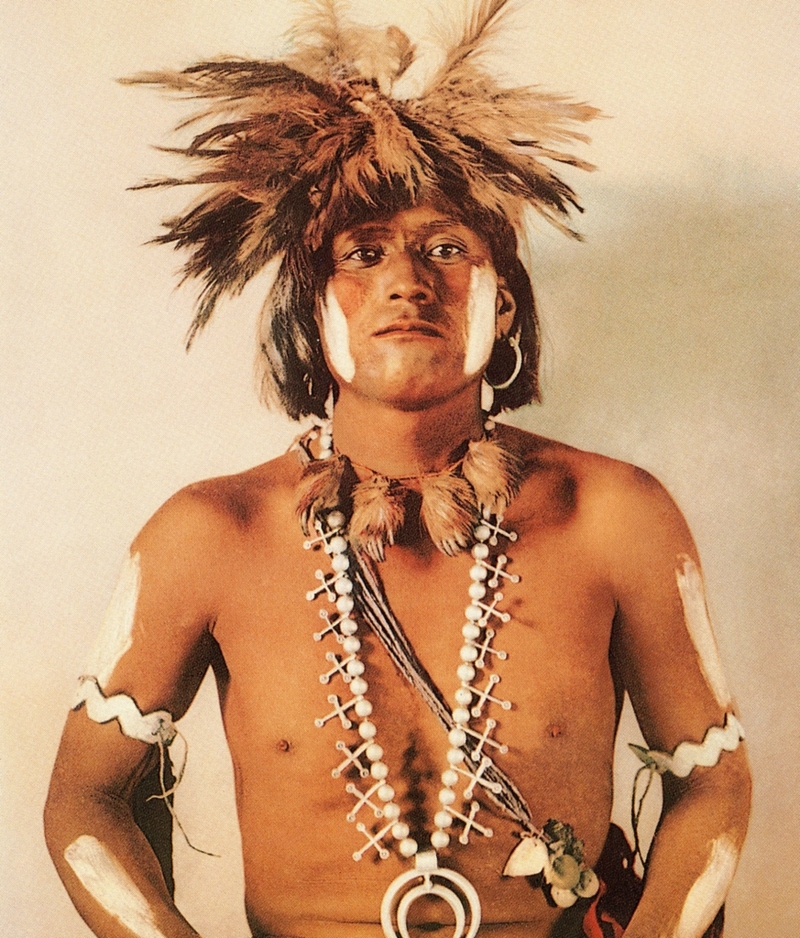

The Rhythm of Nunivak

An inhabitant of Nunivak Island gleefully demonstrates his large drum instrument for the cameraman in this 1930 photo. Nunivak Island lies just off the coast of Alaska and has been home to many generations of Yupik people. These drums, crafted from the bladders or walruses' stomachs, exemplify the Yupik people's resourcefulness and cultural ingenuity.

Ranging in size from small foot-wide instruments to colossal five-foot diameter drums, they served as indispensable tools during winter ceremonies and rituals. Each beat reverberated through the icy landscapes, carrying the collective prayers, chants, and stories of the Yupik, fostering a profound connection between the spiritual realm and earthly existence.

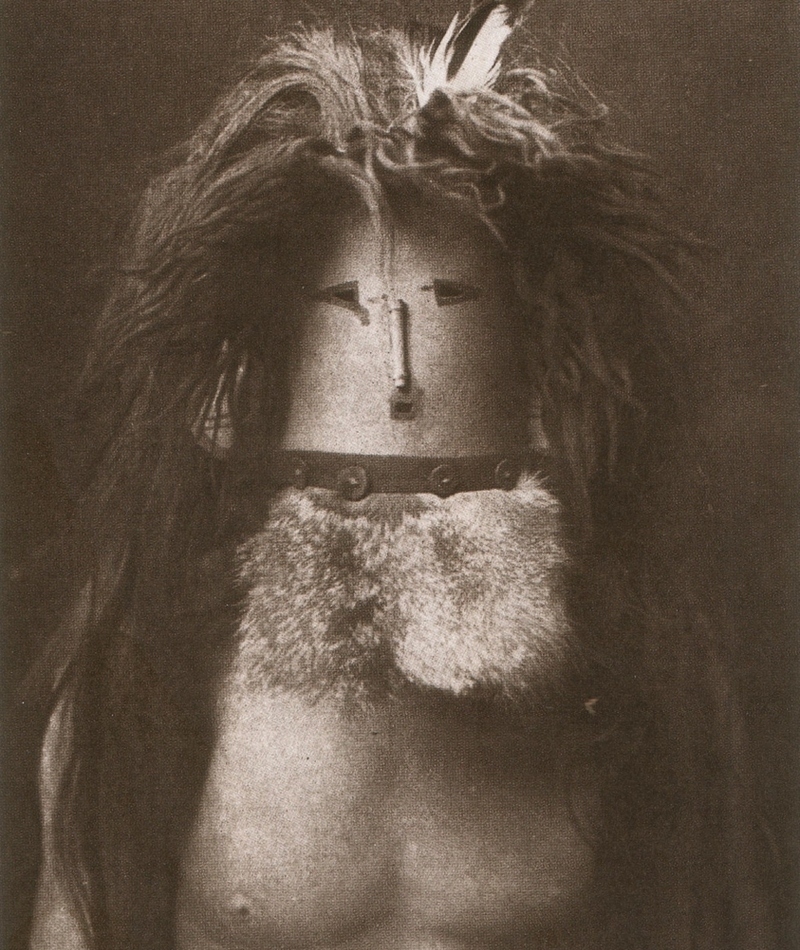

Yupik Man With Eagle Mask

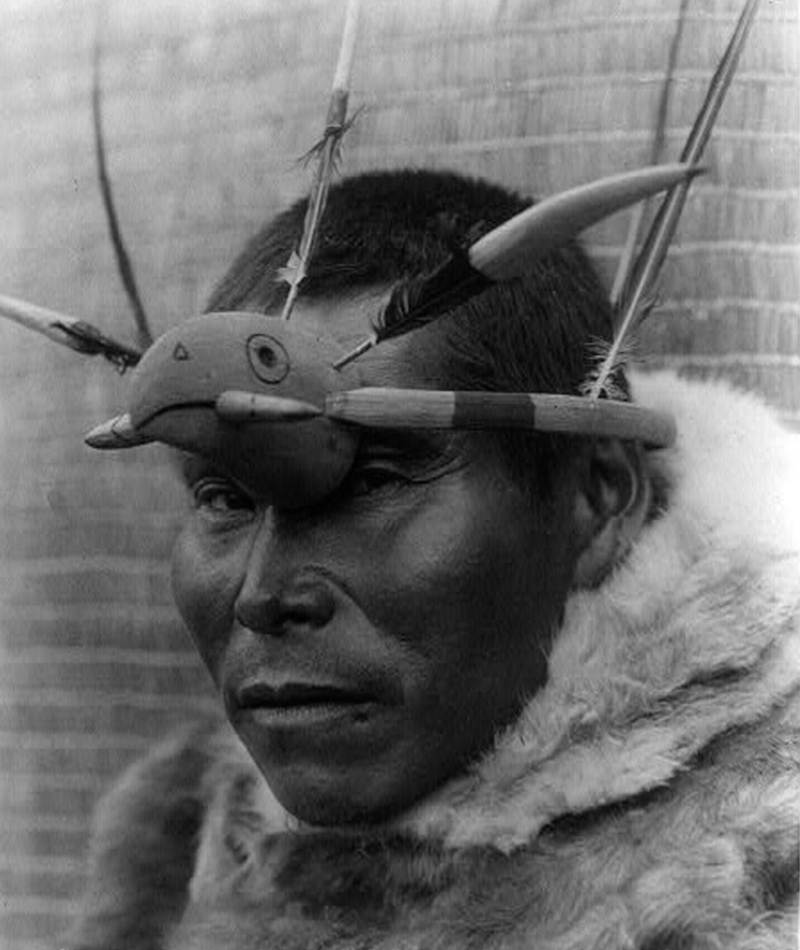

With unwavering resolve, a Yupik man proudly dons a traditional eagle mask, meeting the camera's gaze with a commanding presence. The Yupik people, indigenous to the Arctic, inhabited vast territories spanning from Siberia to the lands of contemporary Alaska, their cultural heritage intricately entangled with the majestic Arctic landscapes.

Being inhabitants of the Arctic meant that the primary source of food for the Yupik was primarily sea mammals, and curiously, the nation did not traditionally fish. Seals and walruses were particularly favored to hunt, and with the acquisition of new technology from the West, whaling also became an activity.

Zahadolzha

During ceremonial occasions, a Navajo man adorns the garb symbolizing Zahadolzha, the deity associated with aiding in harvests. Zahadolzha was one among the pantheon of revered Navajo gods, who were thought to possess unpredictable natures and required continuous appeasement for harmonious relations between humans and the divine realm.

The Navajo's intricate belief system underscored the deep reverence and delicate balance maintained between humankind and their spiritual benefactors, highlighting the significance of rituals and offerings in fostering a harmonious coexistence with the forces beyond the physical realm. "Yei” gods could be summoned by masked performers who would dance in a trance to call their power to the tribe.

Pueblo Pottery

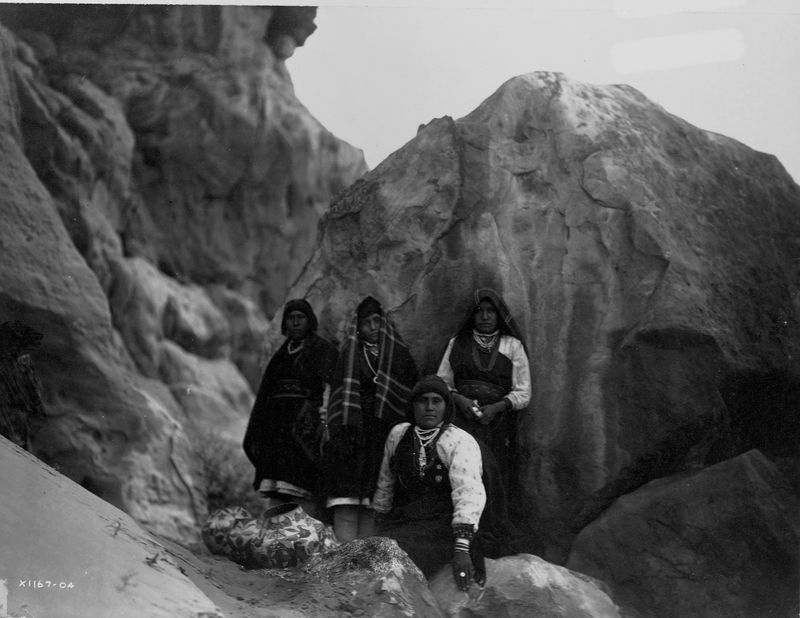

Nestled amidst the rocky landscape of their village, a group of Pueblo Native Americans poses with their pottery amongst the rocks in their village. Pueblo pottery is renowned and is a cultural characteristic of the people themselves, reflecting their deep connection to the land, ancestral traditions, and the enduring legacy of craftsmanship.

The ceramic items were made from clay that was gathered nearby, and instead of using tools such as wheels, the ancient Pueblo people would handcraft every item. One of the most famous Pueblo potters in the 20th century was Nampeyo of Hano, who even had her handiwork exhibited at galleries across the United States.

A Mother’s Love

In this touching 1908 photograph, a captivating scene unfolds as a curious baby stares in wide-eyed wonder at the sudden camera flash. Securely fastened to its mother's back, the child embodies the cherished bond of love and protection, symbolizing the timeless connection between parent and child across generations.

Native American children received a special place in the tribe and would undergo a number of rites and rituals as they became part of the society and world at large. Gender roles were deeply entrenched; boys were expected to learn the art of hunting and defense, and girls were expected to learn how to tend crops, cook, and create tools such as baskets.

Hopi Family

A Hopi family gathers close to a fire being lit in their adobe in this unique colored 1905 capture. Adobes were one of the first permanent dwellings for Native Americans. They were built in large communities called “pueblos,” and the people that built them – such as this Hopi family – would come to be known as “the Pueblo Indians.”

Unlike more nomadic people, pueblos were particularly vulnerable to attack as enemies would always know where to find their targets. One of the largest pueblos in North America is the settlement of the Anasazi people, who mysteriously disappeared.

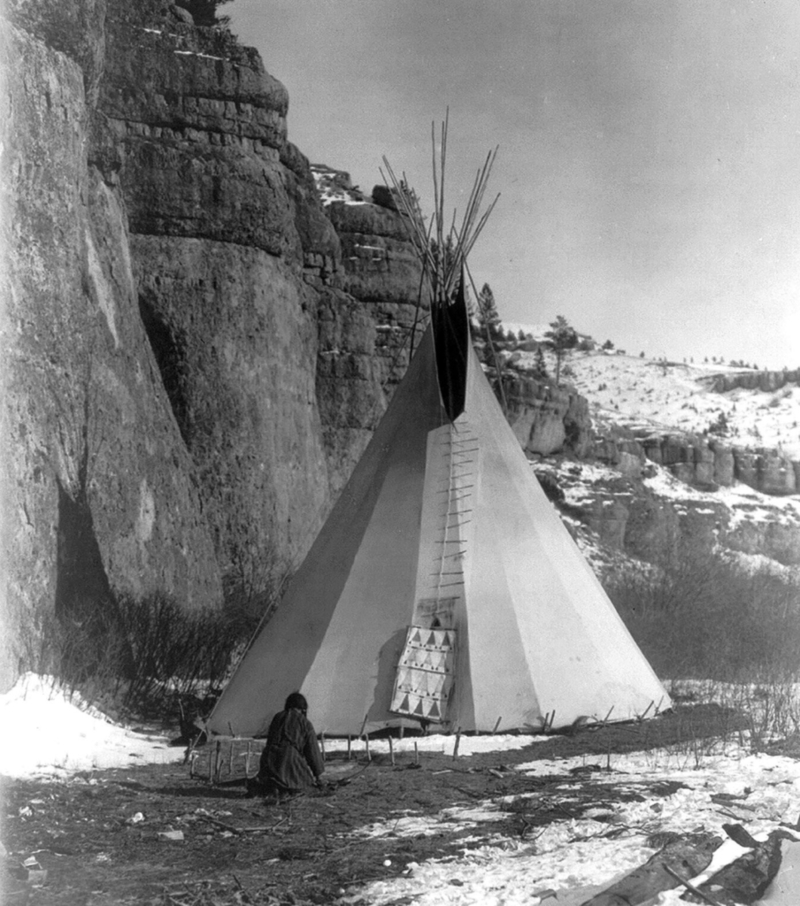

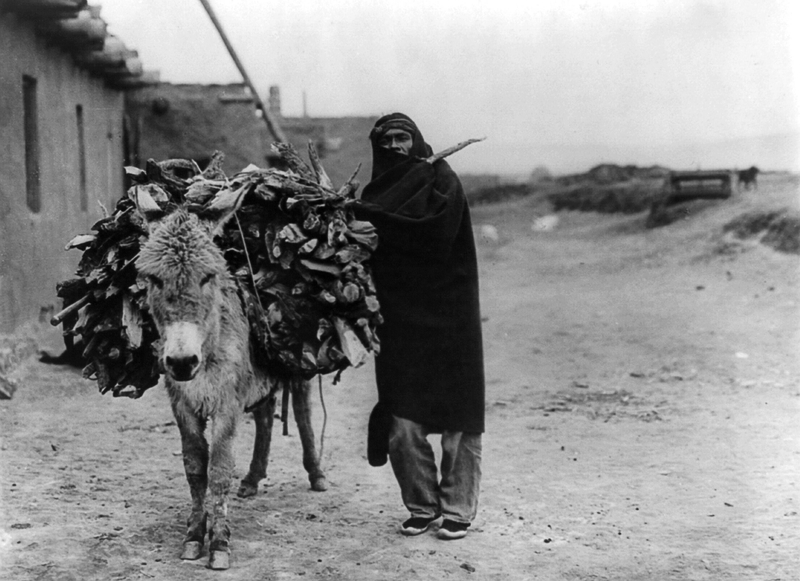

Keeping Warm

As the Native American man nears his tipi, burdened with a weighty load of firewood, the practicality of the structure becomes apparent. While tipis provided shelter, their design presented challenges in harsh winters. The conical shape facilitated the escape of warm air, necessitating the constant burning of firewood to maintain a comfortable temperature within. This symbiotic relationship between the inhabitants and their dwelling reflects the resourcefulness and adaptability of Native American cultures.

Ideally, a winter tipi should be constructed much smaller than a summer one, as the heat radiates much better in the confined space. Ironically, the snow actually helps the tipi stay warm; the snow provides natural insulation and traps heat.

Camping in the Pryor Mountains

Amidst the snowy expanse of the Pryor Mountains, an Apsaroke man resiliently traverses the thick drift, burdened by a bundle of firewood. For countless millennia, these sacred mountains have cradled and sustained diverse Native American nations. Archaeological research reveals an enduring human presence in this region, spanning ten thousand years, a testament to the deep-rooted connection between indigenous communities and this storied land.

From ancient footsteps to present-day traditions, the Pryor Mountains stand as a living testament to the rich tapestry of human history and the enduring resilience of Native American cultures. The Apsaroke still return to the mountains year after year to complete vision quests, a spiritual ascent into the mountains to receive divine wisdom and guidance. Apsaroke people still call the stretch of land “The Backbone of Earth.”

The Rush Gatherer

Edward S. Curtis captures a woman holding a freshly gathered bundle of rush. Rush, formally known as Juncus, is a reed that grows worldwide and is most commonly found at the edges of bodies of water or in very damp, low-lying soil. Humans have utilized rush for millennia.

Native American communities found rush particularly useful for both practical and medicinal uses. The strength of the rush leaf and its flexibility allow for the effortless weaving of items such as baskets. The sprouts and seeds of the Juncus were also consumed to heal a number of health ailments.

Atsina Warriors

The Atsina people were much smaller in number than the surrounding Cree nation and found themselves at loggerheads with the much better-armed and mighty group. Due to this, Atsina warriors relied on stealth more than direct conflict when dealing with attacks.

Dutch and French traders were supplying the Cree and Assiniboines with guns in a trade agreement as the fur industry grew. The far less powerful bow and arrow were no match for the bullets from the Cree, who were driving the Atsina out of their homelands to hunt. In retaliation, the Atsina burnt down two trading posts.

Ojibwe River Hunters

A perfectly timed photograph captures an Ojibwe hunter steadying his bow and arrow, ready to fire at unsuspecting prey. His older compatriot uses a paddle to angle the canoe they are traveling in, his mouth wide as he anticipates the kill. A fellow Ojibwe, Arrowmaker, may have very well crafted the hunter's arrows. The bountiful hunting grounds of the Ojibwe encompassed rivers and lakes, teeming with diverse prey like geese, ducks, beavers, and muskrats.

Their hunting expeditions thrived during the summer, benefiting from the abundance of game and the favorable climate that offered a more hospitable environment for the Ojibwe hunters. With great reverence and skill, the Ojibwe people harmoniously coexisted with the natural world, recognizing the significance of sustainable hunting practices in maintaining their livelihood and honoring their ancestral connection to the land and its inhabitants.

Arrowmaker

In the captivating 1903 portrait, Arrowmaker, a renowned Ojibwe brave warrior, gazes intently with mesmerizing eyes that hold stories of courage and resilience. His name, bestowed upon him in accordance with Native American tradition, signifies his skill and expertise in crafting arrows, a vital art in the Ojibwe culture. Through his piercing gaze and the weight of his name, Arrowmaker's portrait serves as a testament to the Ojibwe's profound respect for craftsmanship, individuality, and the enduring legacy of their people.

In this instance, Arrowmaker was skilled in, well, making arrows! Arrowmaker is also credited with being a “brave” — a man of battle. The Ojibwe fought one of the longest-running battles in North America against the Iroquois nation as they competed for resources in the fur trade.

The Power of the Ojibwe Women

Amidst the lens' gaze, a shining Ojibwe woman graces the frame, her smile illuminating the image. Her poised stance, arms gently interlocked, symbolizes the revered feminine role and power within the Ojibwe nation. In Ojibwe cosmology, the earth embodies the essence of femininity, and the transfer of responsibilities from the planet to her female offspring becomes the very life force that sustains the thriving Ojibwe Nation.

This profound connection between women, the land, and the collective well-being showcases the deep wisdom and reverence the Ojibwe hold for the intricate balance between human existence and the nurturing forces of nature. Obijwe women are honored to be responsible for transmitting cultural practices and overseeing all the affairs that “hold all things together.”

Ojibwe Hunters Make an Offering

With reverence for their Anishinaabe traditions, an Ojibwe man ignites a sacred fire on a hill as his companions observe. As he kneels before the kindling, bow, and arrow in hand, the ceremonial Ojibwe hunting reflects their profound connection to the Creator, Gitchi Manitou. Through this ceremonial act, the Ojibwe honor their spiritual beliefs and the intricate harmony between nature, hunting, and their ancestral heritage.

Hunting was meant to harvest only what they needed for their sustenance, and by sticking to this ancient approach, Gitchi Manitou would continue blessing the nation with abundance. Before a hunt, tobacco would be burnt to petition Gitchi Manitou for a successful hunt.

Chippewa Children

Around a dozen Chippewa children huddle together for a group photo in this photograph taken in the 1890s. The name Chippewa is commonly used in the United States of America to refer to the Ojibwe. Ojibwe is most widely used in Canada, whereas the nation refers to themselves as Anishinaabe, meaning “the original people.”

As one of the earliest Native American nations to engage in land negotiations with European settlers, the Chippewa displayed remarkable adaptability. Land ownership, an alien concept to them, was instead defined by their deep connection to territory and the preservation of natural rights.

A Royal View

Perched on top of the iconic Sherman House Hotel in Chicago, an extraordinary photograph memorializes the presence of three Native American notables. Princess O-Me-Me, a revered Chippewan princess, stands alongside Whirling Thunder, the respected chief of the Ho-Chunk tribe. Completing this remarkable trio is Sun Road, a chieftain hailed by the Pueblo people.

The Sherman House Hotel was a landmark in Chicago, Illinois, at the time and was in business for almost one-hundred-and-fifty years. While the reason for the gathering of royalty at the Sherman House Hotel is unknown, Whirling Thunder is seen elaborating to his royal compatriots about the vast city expanse below and before them.

Chief John Smith Hits the Road

The legendary Chippewa chief, John Smith, embodied an extraordinary blend of courage, vision, and cultural preservation. He is seen here gripping the steering wheel of his car with a smiling passenger in tow in this 1920 snap. Chief John Smith was a celebrity around his native Minnesota and would partake in modern life although very advanced in age.

While Traveling around his hometown of Cass Lake, he would keep autographed pictures of himself to sell to admirers. Chief John Smith maintained close personal and business ties with his colonial neighbors and assimilated into the rapidly expanding European way of life, even converting to Catholicism in 1914.

Ojibwe Maiden

A young Ojibwe woman, dressed in the distinctly colorful attire of the Ojibwe, sits on a mat for her photograph. The Ojibwe peoples inhabited what today is southern Canada and northern America. The nation remains one of the largest population groups of Native Americans, second only to the Cree.

The Ojibwe did not rely on the far more common social hierarchy of a dominant chief but instead was primarily self-autonomous, with each family headed by a paternal figure. The different clans of the Ojibwe would spend autumns and winters hunting and reunite with the nation at large in summer.

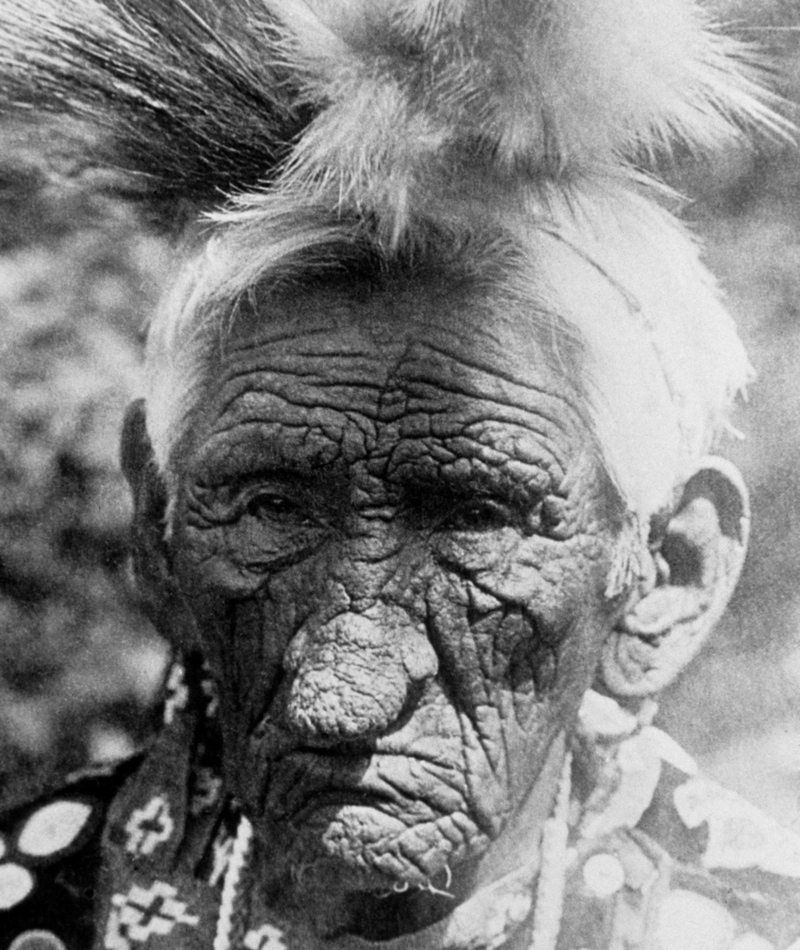

Chief John Smith

Chief John Smith’s wizened stare looks at the horizon past the camera in this 1920 photograph, two years before his passing. Chief John Smith, head of the Ojibwe tribe in Minnesota, lived a famed and fabled life. He was a respected leader known for his wisdom and diplomacy. His guidance brought unity and prosperity to his community, leaving a lasting legacy of strength and compassion.

The centenarian’s prominent and unusual wrinkles led some to believe claims that Smith had been one-hundred-and-thirty-seven years old at the time of his death in 1922! Other reports figure him to have died between ninety and one hundred years old. Despite being married to eight women, Smith sired no children.

Bagobo Chief

In 1904 during a St. Louis fair, a captivating photograph emerged, showcasing the youthful allure of Datu Bulon, the 19-year-old Bagobo Chief. Recognized for his remarkable physical beauty and flowing tresses, he stood out among his fellow Chiefs as the most captured subject by photographers.

As the fair concluded, whispers circulated that he joined a troupe of entertainers, embarking on a tour across the United States. Although covered in rumor, his story resonates with the enigmatic charm of a cultural icon exceeding borders, leaving behind a legacy that continues to delight and captivate those drawn to the timeless artistry of photography.

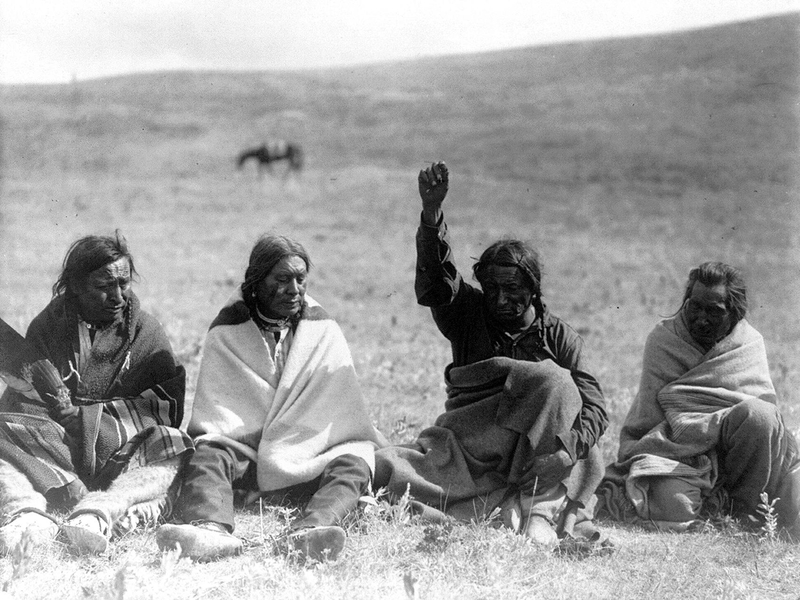

On the Custer Outlook

Famed photographer Edward S. Curtis known for his iconic portraits breaks the fourth wall as he captures himself in a poignant image. Curtis sits on his knees between four Apsaroke men who all return equally solemn stares into the camera.

The title of the image, “On the Custer Outlook,” is significant as Curtis sits with four Apsaroke scouts, just like the notorious American General Custer did many years prior in the exact location. General Custer employed Crow scouts to help him attempt victory over the Sioux at Little Bighorn, a battle that would cost Custer his life.

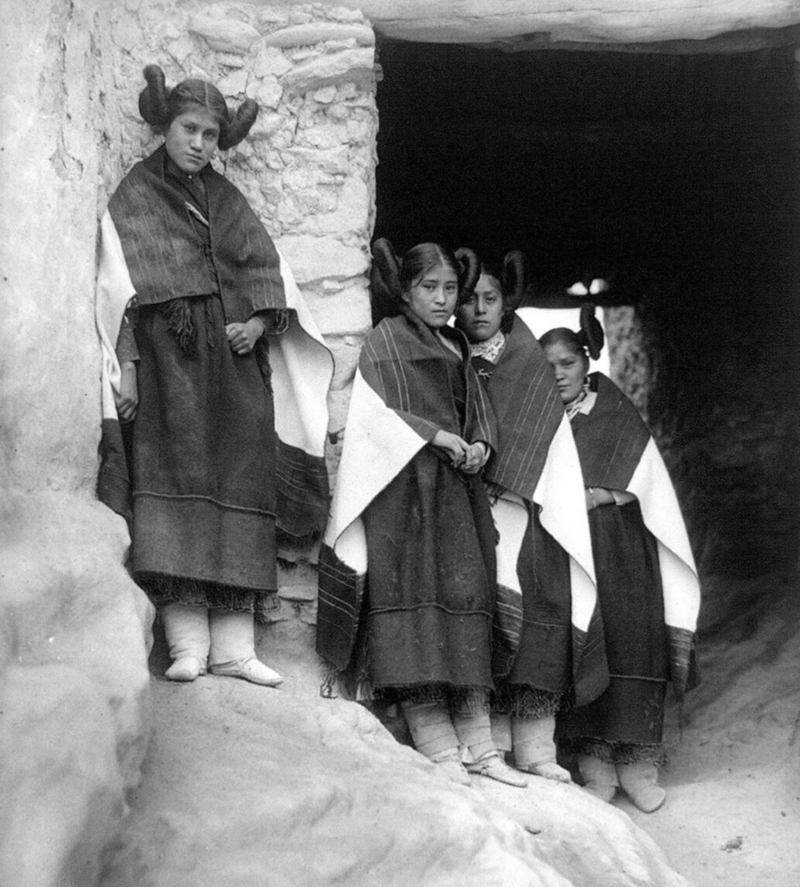

Hopi Women Grind Corn

A Hopi woman looks up into the camera flash as she grinds corn alongside her three compatriots. Hopi women were easily identified by their distinctive hairstyles, which was unique and different than all other tribe women's styles. The well-defined circular hairstyle is known as the “squash blossom whorl” or “butterfly whorl.”

Unmarried maidens were The only Hopi women who wore their hair in this style. In order to achieve the creative whorl, the maidens’ mothers would tightly wind their hair around a circular piece of wood. Once the wood was removed, the ends of the hair would be tucked in place, and the shape would remain.

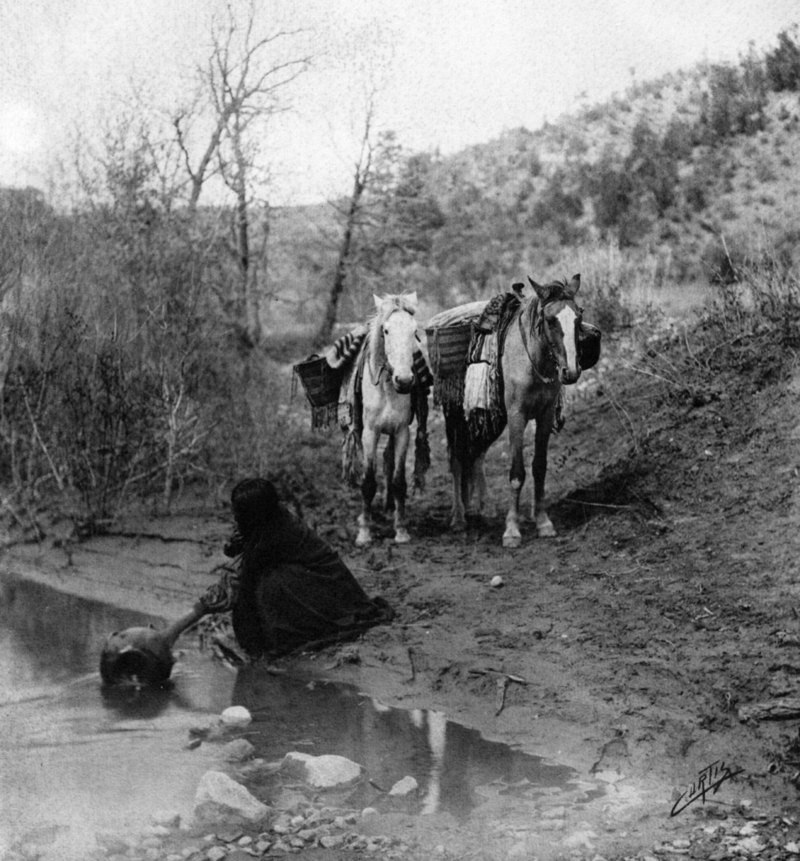

Bullchief Crossing Shallow Rapids

Venerated Apsaroke chief Bullchief guides his trusty steed through a river in this 1905 picture taken by Edward S. Curtis. Bullchief’s history is a true hero’s journey. His early career as a Crow warrior saw him earn no honor from warfare, and he returned home after each raid or battle empty-handed.

After a period of intensive fasting, Bullchief began to see visions that he would later credit with bestowing him with military might. At the time, “counting coup” was a form of enemy surrender that earned the highest praise, and Bullchief prided himself on holding the record.

Arikara Chanting

Arikara men, part of the Arikara tribe, were known for their prowess as hunters, warriors, and skilled craftsmen. They exhibited resilience, leadership, and a solid connection to their cultural heritage. Here we see six of them standing in a row, rattling and chanting a sacred hymn during a medicine ceremony in 1908. The Arikara take their name from mimicking buffalo horns by placing two bones on either side of their head and wrapping them in hair.

The migration of the Sioux and the westward advance of American pioneers saw the Arikara face a devastating blow to their livelihood. Generational conflict with the Sioux saw the Arikana driven out of their homelands, and smallpox ravaged the small community when European traders made contact with them.

Hansen Harvesting

In the radiant desert landscape of the southwestern region of North America and northern Mexico, three women, most likely belonging to the Qahatika nation, return with their bounty of Hansen fruits. Hasen is a fleshy, pear-like fruit that grows on the saguaro cactus in the southwestern region of North America and northern Mexico.

The second woman's carrier is known as a “kiho” and was particular to the Qahatika. The Hansen fruit is sweet and can be eaten fresh or dried. The Pima – relatives of the Qahatika – is known for making syrup and a fermented drink from it.

Dakota Man With Calumet

When French missionary Jacques Marquette encountered the calumet, commonly known as the peace pipe, he wrote, “There remains no more, except to speak of the Calumet. There is nothing more mysterious or more respected among them.

It seems to be the God of peace and of war, the Arbiter of life and of death.” The calumet was pivotal in sealing contracts between tribes and tribespeople for millennia. A smoking bowl was carved out of a hard, red rock known as catlinite. A long stem would then be attached to the bowl in order to draw smoke from the burning tobacco.

Salish Women Preparing Meat

Peckish hounds watch a group of Salish women strip, slice, and dice meat brought back from a successful hunt on the plains in this 1910 Edward S. Curtis photograph. Game meat was highly prized among the Native America, First Nation, and Inuit nations of early America.

One of the most essential roles in each tribe was to be that of the cook. A good cook earned great stature and praise for their perfectly roasted, boiled, and prepared dishes. A curious way to prepare food was to wrap the meat in clay, let the clay harden in a fire, and then break open the vessel.

Benoit

Native American Mrs. Benoit is captured in a somewhat heartbreaking image by American-Danish photographer Jacob August Riis crocheting rugs. Not much information is provided about Mrs. Benoit besides being widowed and living in an attic in Manhattan.

Riis published the photo series “How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York” in 1890 which turned out to be a groundbreaking work, documenting the harsh living conditions of immigrants and the impoverished in late 19th-century New York City. The photographer found himself a victim of the failing economy at the time and had to move into the impoverished tenements, giving him a first-hand experience of the struggles.

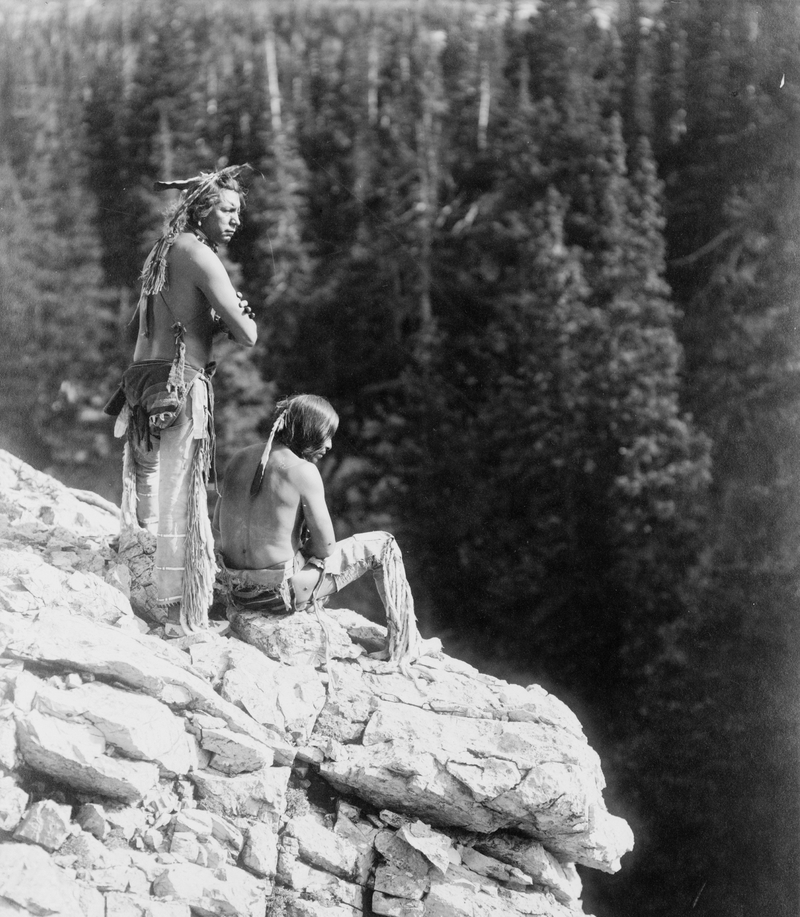

Looking Over Cliff

Two Native American men gaze out over the vast open plains from a cliff face in this 1912 image, scouting for prey. Hunting complemented the Native American and First Nation diets of gathered berries, fruits, vegetables, and aquatic protein such as clams, mussels, and fish. Only the Inuit tribes are known to survive almost exclusively on their hunt due to the climate being inhospitable to agriculture.

For Native Americans that lived on the Great Plains, looking for bison and buffalo from the tops of cliffs was a favored method of hunting. Over all the Native Americans hunted a variety of animals for nutrition, clothing, and tools. Common game included bison, deer, elk, rabbits, birds, and fish, with hunting techniques varying across tribes and regions.

Hopi Bride

A Hopi bride dons her wedding dress for this 1922 portrait taken by Edward S. Curtis. A Hopi bride’s garments were weaved by the male relatives and male friends of the groom. That’s right – the groom’s party sewed to the wedding dress!

The bride’s “dress” would be two long robes. The groom’s relatives would deliver the robes to the bride wrapped up in reed, along with a sash that resembled a bunch of tassels and very plump, healthy ears of corn. Corn was seen as a blessing of fruitfulness for the Hopi and ensured fertility.

Piegan Medicine Pipe

The Native American medicine pipe, also known as the sacred pipe or peace pipe, holds deep spiritual significance. It is used in ceremonies and rituals to communicate with the spiritual realm and bring harmony and prayer to the community. A solemn Piegan man kneels for his portrait while presenting a highly decorative medicine pipe.

The medicine pipe is central to the healing arts of the Piegan (and Blackfeet nation in general), and lore has it that the sun blessed the nation with its first pipe. The pipes would be decorated with feathers, fur, and, in some instances, carvings. A medicine pipe, although sacred, could be sold, and the price was usually paid in the form of up to thirty horses for a single pipe.

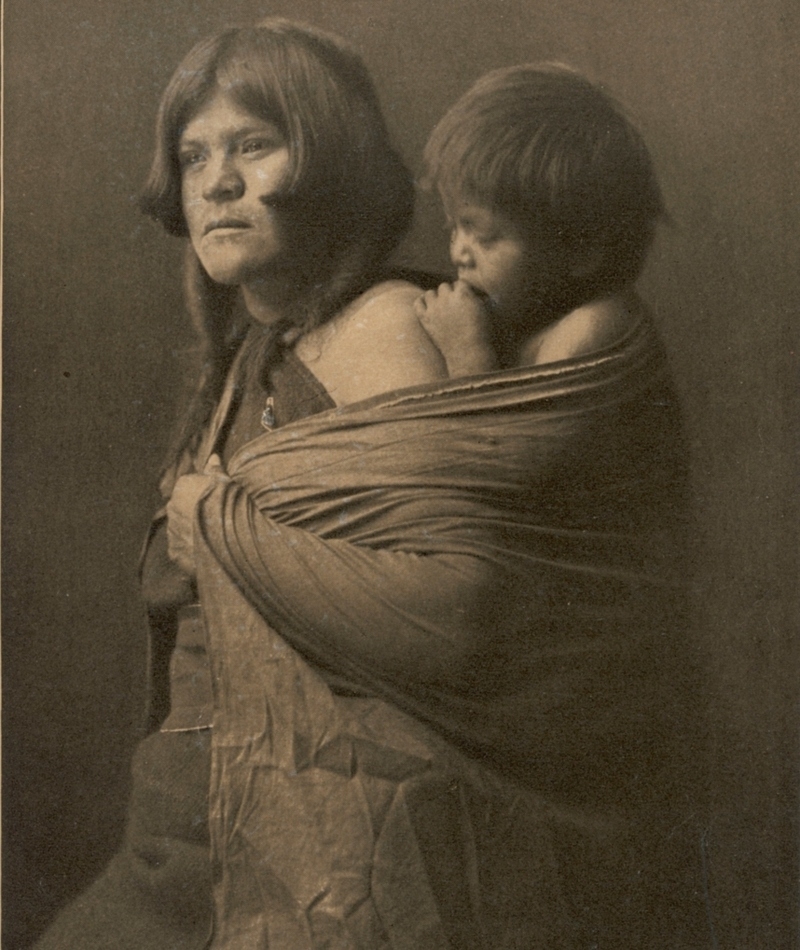

Hopi Child on Back

A Hopi child snuggles against their mother in this 1900 portrait. Hopi children go through a ritual of initiations starting with their very first days in the world. For almost three weeks after birth, their mother and the elder tribeswomen kept a Hopi child wrapped up and sheltered. Two perfect ears of corn would be set on either side of the child, and the Hopi mother and grandmother blessed one each.

The child would only receive their name twenty days after being born in an intimate naming ceremony amongst the women. The baby's name often reflects essential elements such as family heritage, nature, spiritual beliefs, or significant events, symbolizing a connection to their culture and identity from the earliest stages of life.

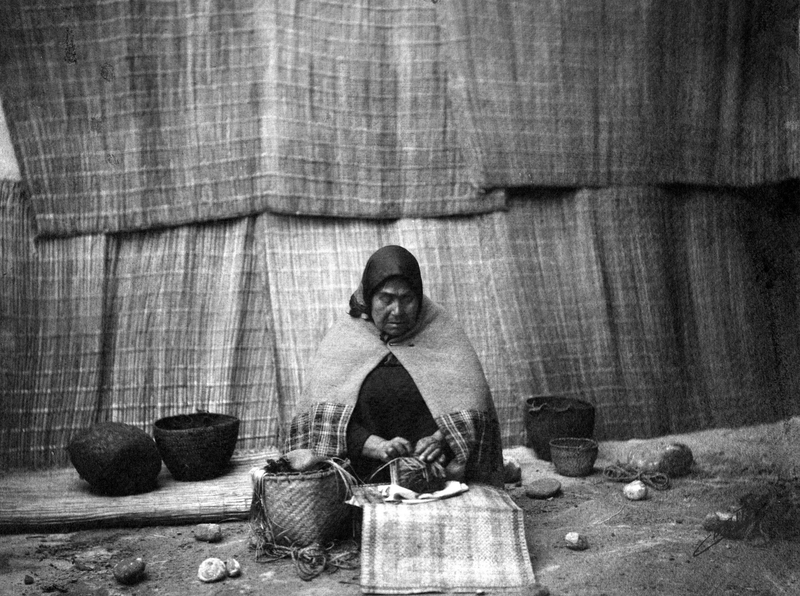

Basket Weaving

Basket weaving holds deep cultural significance for Native Americans, representing both practical and artistic expression, and they carry traditional stories and skills through generations. Here Edward S. Curtis takes a candid snap of a Native American woman diligently weaving a basket in this 1899 photograph. Basket weaving was a standard art form across almost every single Native American and First Nation culture.

The versatility of baskets was essential to survival. Plaiting, twining, and coiling were the most common techniques for creating baskets. Baskets were used for everything from gathering food to carrying clay, building sand, and drying meats. The construction of huts essentially followed the same basket-weaving techniques.

Wedding

A couple shares a smile with a First Nation chieftain as he bestows matrimonial rights upon them in this 1929 photograph. First Nation weddings were a complicated affair, and the preparation for the wedding began long in advance.

As the couple intended to become wed, they had to choose respective counselors known as “sponsors.” The sponsors' commitment was to provide lifelong guidance to the couple as they navigate marriage. At the ceremony itself, the company made their vows to the Creator instead of to each other and would share a smoking pipe to conclude the marriage.

Register to Vote

Native Americans queued to vote for the first time after being granted voting rights in 1924. There is a long and convoluted history behind the status of enfranchisement and rights for Native Americans in colonial America which involved numerous obstacles and discriminatory practices in exercising their right, including literacy tests, poll taxes, and other forms of voter suppression.

The government at the time believed that no Native American could vote unless fully assimilated, but enfranchisement only came in the form of self-governance. This excluded self-governing Native Americans from federal policies and citizenship rights. The Snyder Act of 1924 overturned this archaic law and bestowed unimpeded voting rights to all Native Americans.

Esau Prescott

Esau Prescott strikes a pose for the lens of Charles van Schaik in this 1915 capture. Esau Prescott belonged to the Ho-Chunk tribe and is seen in this photo in full school uniform as he was forced to attend boarding school in Black River Falls, Wisconsin. The federal policy of sending Native American children to boarding schools became rampant in the 19th century as it aimed at assimilating them into Euro-American culture.

Wisconsin alone had eleven schools dedicated to this, which disrupted their traditional way of life and had lasting impacts on their cultural identity and communities. Esau would have attended the Winnebago Indian Mission School, administered by the Reformed Church of the United States.

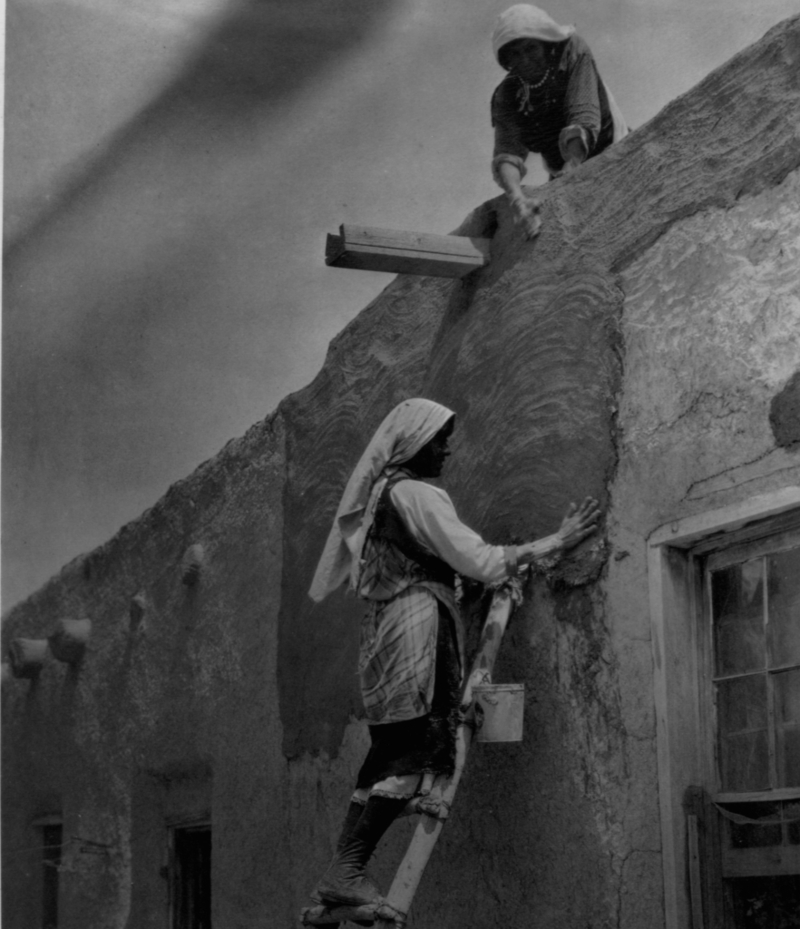

Paguate House

Two women assist each other in plastering the front of a house in Laguna Pueblo. The area in which the Laguna Pueblo is situated has been inhabited for close to seven thousand years. Life at Laguna Pueblo revolves around a strong sense of community and the preservation of cultural traditions.

A famous mission was set up in Laguna Pueblo in 1699 and is regarded as one of the most well-preserved historic buildings on the North American continent. Interestingly, many Native Americans who lived in Laguna Pueblo adopted the very Irish surname of Riley. This was mainly in part to forced assimilation.

Yurok Man in Canoe

A Yurok man brings a canoe to shore in this 1923 photogravure. The Yurok traditionally occupied most of northern California. Their social hierarchy was unique as they sought no specific positions of power, and each family was intended to manage themselves and primarily see to their own needs.

Each household would claim a piece of resource-rich land and share it diplomatically with other community members. The value of life and the worth of individuals were determined by the wealth they had accumulated. Shamanism was practiced only by female members of the tribe, earning them great respect within the Yurok community.

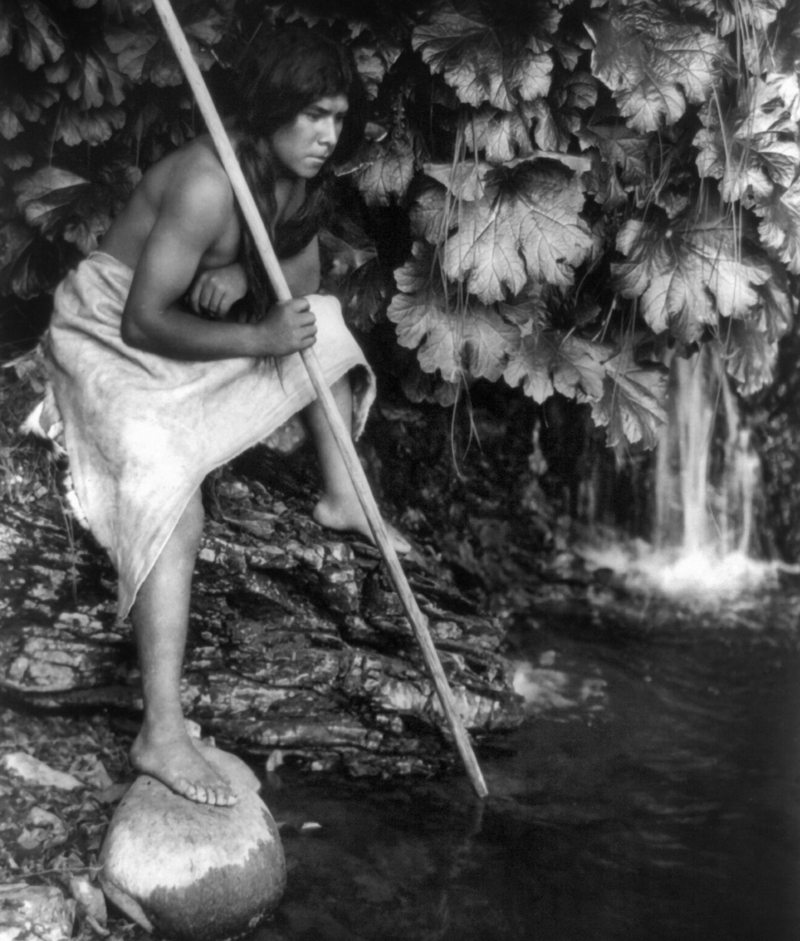

Hupa Man Spearing Salmon

A Hupa man stands in a river, spending a solitary day catching salmon with his spear. The Hupa people inhabited what is now modern-day California and were mostly centralized around the Trinity River. They were mainly characterized by their intricate basketry, vibrant ceremonial dances, and deep connection to their ancestral lands.

The Hupa had a unique culture in that it combined different aspects and practices of Californian and Pacific Northwest native cultures. Living in the interior of the country, the Hupa cultivated a trading economy with coastal Native Americans and would trade acorns primarily for seafood from the coastal communities.

Kwakiutl Crests

The Kwaikiutl people, also known as Kwakwaka'wakw, are indigenous to the Pacific Northwest. Here are two intimidating totem poles that stand at the entrance of a Kwaikiutl’s house in what is now present-day Alert Bay in British Columbia. The totem poles serve as family crests, symbolically protecting the home's entry while displaying the homeowner's status.

The eagle, with wings spread wide and eyes focused on the horizon depicts the paternal crest. The lower half of the totem poles have grizzly bears as the maternal crest. In the firm grip of the grizzly bears is a rival chieftain’s head, symbolizing the crushing of the Kwaikutl’s enemies.

Wasp Costume

The Quagyuhl men were esteemed for their exceptional woodcarving abilities, creating intricate totem poles and masks that showcased their artistic prowess. The Qagyuhl man cuts an intimidating figure in his Hamasilahl costume. Hamsilahl loosely translates as “wasp-embodiment,” as the god was personified in elaborate ceremonial dances.

The Qagyuhl, unlike many other tribes of the time, did not protest outsiders observing their rituals and sacraments, allowing famed photographer and ethnologist Edward S. Curtis to witness and document some of their sacred rites. Curtis noted that the Quagyuhl invested heavily into the creativity of their spiritual practice and had the most extensive and diverse range of masks, costumes, and customs.

Absaroke Warrior

An Absaroke warrior is mounted on his steed. His bow and arrow are at the ready while he looks out at the plains below him in this 1910 image. The Crow nation identifies as “Apsáalooke,” meaning the children of the large beaked bird. The role of the horse was central to the Crow, and they were renowned for having the largest herds of horses.

An annual festival would take place on the plains whereby different tribes would bring their horses to display status and power. This parade persists to the modern day; up to fifty thousand participants attend each August.

Cayuse Mother and Child

The Cayuse people were also known as Weyiiletpuu, “the people of the ryegrass,” to their neighbors, the Nez Perce. They were a relatively small but highly influential tribe of the Pacific Northwest region of North America. Combining commerce and skilled warfare, the Cayuse were well known for forming alliances with other tribes and European settlers.

A curious relationship developed between the Cayuse and Christian missionaries as the former was curious about the “white man’s book of heaven,” that is to say, the Bible. A dispute between the evangelists and Cayuse triggered the first “Indian War” of the Pacific Northwest in 1847.

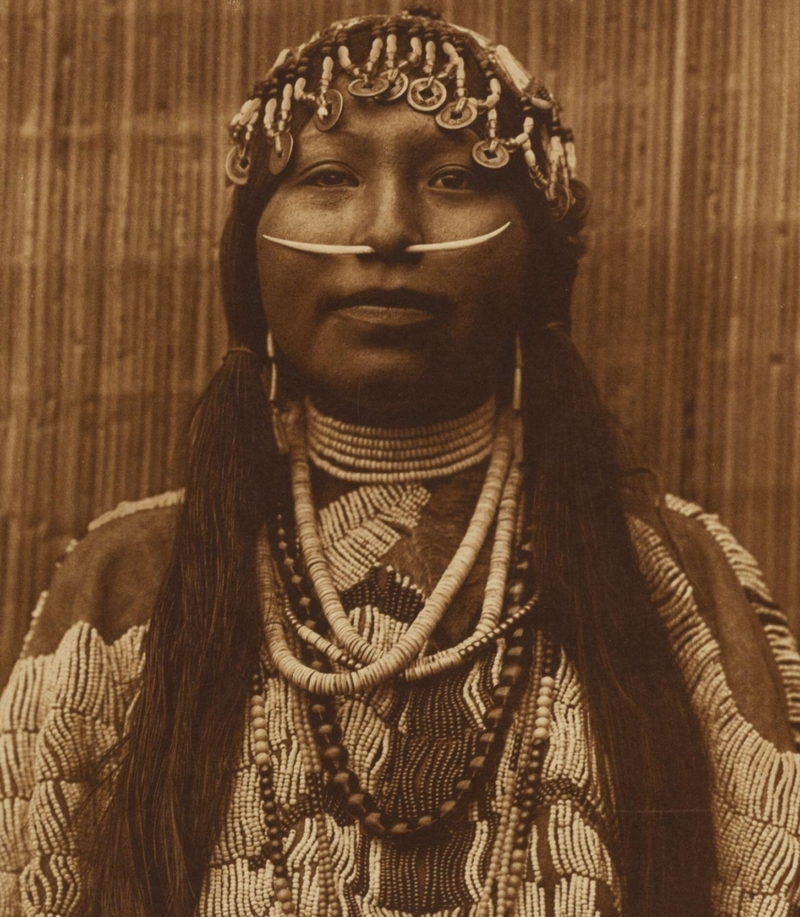

Wishram Woman With Nose Piercing

A Wishram woman, known for their exceptional basketry skills and beautiful designs, displays her jewelry to the camera with a particularly striking dentalium shell nose piercing. Dentalium shell was a highly coveted material for First Nation, Native American, and Inuit peoples and was extensively traded. As a rare material, the decorative shell denoted nobility and would usually be worn by women of high standing within the tribe.

The Nuu-chah-nulth people, who inhabited the Pacific Northwest region of America, were the primary harvesters and distributors of the precious material as they had direct access to the coastal plains on which it was abundant.

Piegan Women

Two Piegan women share a quiet moment overlooking a glassy lake in this 1911 capture by Edward S. Curtis. Piegan women held a prominent place in the Blackfeet community. The term “manly-hearted woman” was applied to the Piegan women.

It denoted them as fiercely independent and, in contrast to the role of many other Native American women at the time, free to make their own decisions and live alone if they so wished. An age-old tenet of the Piegan woman in relation to her husband was “sits beside him" instead of “sits behind him.”

Two Whistles

A 1909 photograph shows a Mountain Crow man named Two Whistles with a medicine hawk, his spirit animal, adorned atop his head. Two Whistles was undoubtedly an ambitious warrior. His daring antics began at the age of eighteen when he led two other compatriots in a raid against a Sioux camp that resulted in capturing one hundred Sioux horses.

Two Whistles would fight against the Arapaho and engage in further skirmishes with the Sioux. At the age of thirty-five, Two Whistles underwent a multiday fast, claiming that the moon revealed where he could find unlimited horse and bison.

Apsaroke Hide Stretching

An Apsaroke woman prepares hides for tanning and stretching in this 1909 photograph. Every Native American tribe had a process of preparing hides. The methods differed from region to region and people to people, but all achieved the same result: supple, soft, and luxurious hide or leather.

Preparing the hides underwent four phases: fleshing, dehairing, tanning, and smoking. In the fleshing phase, all meat and stubborn fat needed to be removed. To make the hair removal process easier, some traditions would soak the hide in a mixture of water and ash. The hides would then be tanned and smoked in order to be waterproofed.

Taqul the Moki Snake Priest

A shaman, known only as Taqul, stares sternly into the camera for this awe-inspiring 1902 image. Taqul was dressed in his “snake priest” attire. Snake priests were part of the Moki people and performed one of the most death-defying rituals documented.

Once a year, snakes as venomous as rattlesnakes and as non-deadly as bull snakes would be captured alive and brought to the small village in what is now modern-day Mexico. Priests would perform elaborate dances and performances with the reptiles to the astonishment of hundreds of spectators. Reports claim that no priest ever suffered a snake bite.

Apache Woman Drawing Water

A lone Apache woman sits on her haunches drawing water from a river in an unknown location in this 1903 photograph. In a similar fashion to the Sioux, the Apache nation is a large conglomeration of many different ethnic tribes that came to be one nation under the Apache banner.

The immense kingdom of the Apache started in Colorado and ran through New Mexico, Texas, and Arizona, and even comprised some of the Mexican states of Sonora and Chihuahua. Due to the diverse terrain the Apache inhabited, they employed a number of different activities that complemented their economy.

Young Sioux Woman

A young Sioux woman strikes a graceful pose in her full traditional dress. The Sioux are not one distinct nation but rather a coalition of several tribes who share the same linguistic root and were revered for their strength, resilience, and integral role within their society.

The Sioux name itself is a contraction of the word “Nadouessioux,” the name was given to them by the Ojibwe tribe meaning “the enemies,” due to their long history of intertribal conflict. The Sioux grew to be one of the largest militias in northern America and were even recruited to fight in the American Civil War.

Young Hopi

Four young Hopi women pose for this photograph taken at Walpi village at the turn of the 20th century. The Walpi settlement is one of the oldest continuously inhabited settlements in the continental United States. The village was relocated to try and defend against encroaching Spanish colonists and still retains most of its original architecture today.

The Hopi people began moving out of the settlement into more modern housing arrangements in the later years of the 20th century, and Walpi today is used for ceremonial purposes. The Hopi tribe was best recognized for their rich spiritual tradition, a deep reverence for nature, and prioritization of community harmony and balance, which sometimes overcast other tribes in their surroundings.

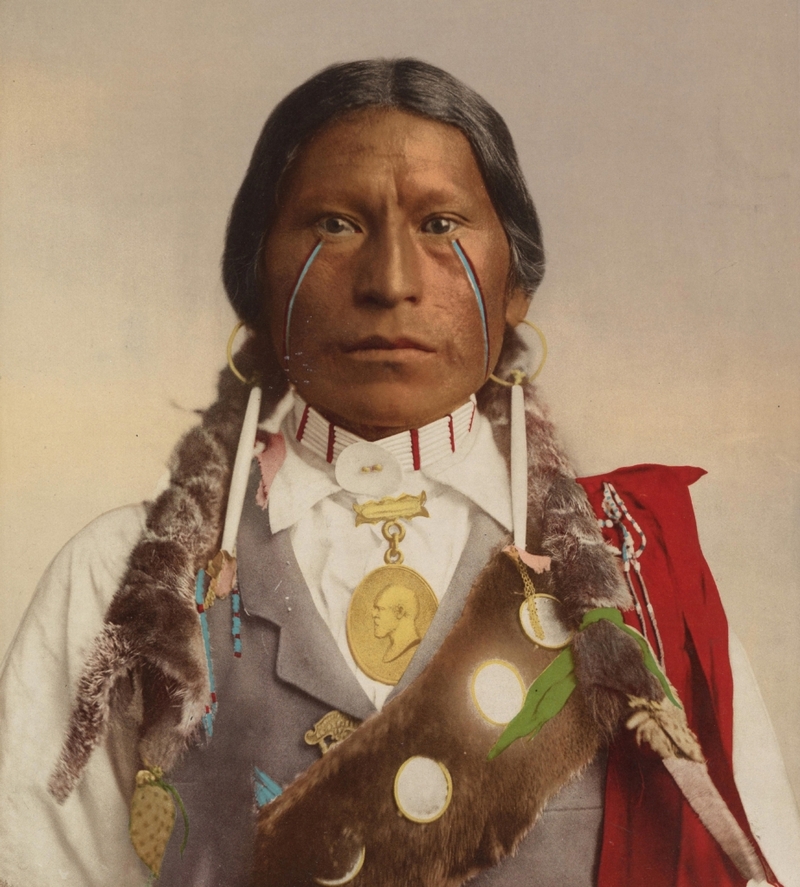

Chief Garfield Medal

A Jicarilla chieftain wears a medal bearing the profile of then-American president James A. Garfield. Upon receiving the medal, the tribal leader changed his name to “Chief Garfield.” President Garfield awarded the medal to Chief Garfield in recognition of his peacekeeping efforts between the Jicarilla people and the United States government. Chief Garfield would later go on to adopt the same Spanish surname of Velarde.

The photo sees him donning a European waistcoat and collared shirt while at the same time wearing his Jicarilla sash and shell necklace. The Chief was associated with so many significant momenta, however, he is best recognized for playing an essential role in preserving his people's cultural heritage and advocating for indigenous rights.

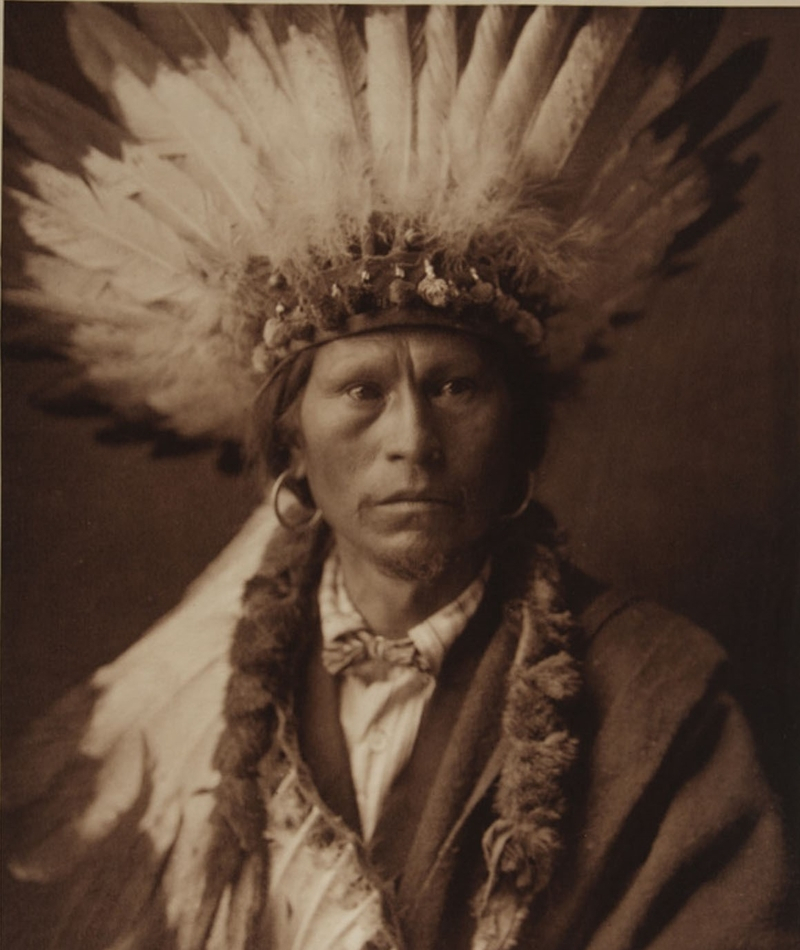

Chief Garfield

A Jicarilla chieftain who took the name of “Chief Garfield” strikes a somber pose in this 1907 image taken by Edward S. Curtis. He was a respected and influential leader of the Lakota Sioux tribe and was known for his wisdom, diplomacy, and dedication to his people. Adorned in feathers, both as a headdress and a sash, braided hair wrapped in fur sleeves, and large hooped earrings, the chief fits the standard of the time.

His original name is lost to history as he, upon receiving recognition from American President James A. Garfield, changed his name to that of the president. The next time the chief would be photographed, he would be in full European attire.

Buffalo Dance

Following in the tradition of many ancient celebrations, the Buffalo Dance, sometimes referred to as the Bison Dance, is an annual celebration to mark the return of the buffalo to the northern plains after a long, cold winter. It is a sacred and influential Native American ceremonial dance that honors the buffalo, symbolizing abundance, strength, and connection to the natural world.

The dance is performative and is intended to invoke supernatural forces to keep the cycle of the buffalo migration and return in place. One of the first video recordings of Native Americans was filmed in 1894. The sixteen-second clip shows three Sioux men dancing while two others beat drums.

Haschogan, the Hunchback God

The Navajo Nation, the largest Native American tribe in the United States, is primarily located in the southwestern regions of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah and is known for its rich culture and deep spiritual traditions. Here is a Navajo man who wears the mask of Haschogan, the hunchback god. Petitions were made to Haschogan to ensure a bountiful harvest each year.

The nickname “the hunchback” comes from the position of being bent over in a field while sowing seeds. It is believed that Haschogan’s back contains rainbows and mist and will be released on the fields of the Navajo after winter. The Navajo, as do all other Native Americans, have a pantheon of gods and goddesses, each with their individual traits and abilities.

Feast of San Esteban

This next photo might b a little blurry, however, the story behind these people is still very much visible. A group of Acoma people takes part in a procession to celebrate the feast of San Esteban in this 1926 photograph. The annual banquet is celebrated in the Acoma Pueblo.

While the pueblo is mainly uninhabited, many Acoma people return to it for the commemoration ceremony. The event is meant to honor San Esteban, or Saint Stephen in English, as instructed by a catholic friar who won the trust of the Acoma in the 17th century. The event entails a full day of dancing, with each group performing a different dance routine.

Kwakwaka'wakw Eclipse Dance

A group of about a dozen Kwakwaka'wakw men joins together in a ceremonial dance to coax the sun out during an eclipse in this black and white photograph. The Kwakwaka'wakw are a first nation indigenous to the coastal areas of modern-day British Columbia in Canada.

Originally recorded as Kwakiutl, the nation changed its name in the 1980s to reflect its linguistic identity better. The group is renowned for its creativity and highly elaborate dances. The Kwakwaka'wakw identify themselves according to which “band” they belong to, bands being distinct groups within the nation itself: Eagle, Wolf, Raven, or Killer Whale.

Flathead Encampment

The name of these particular people, the Flathead, is misleading as there is no record of them engaging in the ancient practice of head flattening. Instead, the nation was better known as “Salish” — the people. The Salish found themselves deprived of access to many natural resources after the much larger Blackfoot tribe prevented them from hunting bison and buffalo.

At the same time, European colonists began large-scale trapping operations, which left the Salish outnumbered. Today, the Salish primarily reside in a one-and-a-half million-acre reservation in Montana and are engaged in a variety of activities, including fishing, hunting, gathering, arts and crafts, cultural events, and advocating for indigenous rights and environmental stewardship.

See Hawk

A Nimi’ipuu man poses for the lens in this shot. Little is known about the subject of the photo, See Hawk. His tribe, the Nimi’ipuu, was incorrectly named “Nez Perce” by French explorers in a case of mistaken identity. The phrase “nez perce” translates to “pierced nose” in English, as some Native American tribes were known for this facial adornment.

The Nimi’ipuu became a force to be reckoned with after learning how to domesticate horses. They managed to fend off five thousand American soldiers over a six-month-long battle that came to be known as the Nez Percé War.

Blackfoot People in Tipi

A 1933 photograph captures three Blackfoot individuals preparing food in their tipi in Glacier National Park. The Blackfoot Nation and Glacier National Park have a long history. Dubbed “the backbone of the world,” the area is the ancestral home of the almost one hundred thousand Blackfoot alive today.

The vast territory dominated by the Blackfoot in the 18th and 19th centuries stretched from modern-day Saskatchewan a thousand miles south to the Missouri River. Today, members of the Blackfoot nation have set out to reintegrate Glacier National Park as part of their homelands and income.

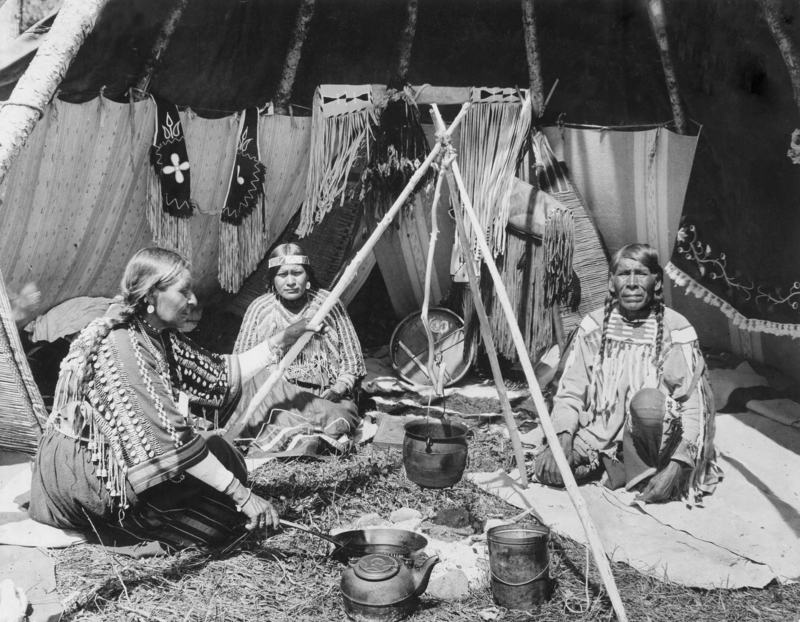

Atsina Elders

In this unique photograph, there are four Atsina elders who share a moment in this 1909 photograph. The Atsina people went by many names, including A’ane, Ahe, and A’aninin. The nation personally referred to themselves by the latter, meaning “The White Clay People.”

A curious history of French interaction emerged as the French added yet another name to their already sprawling list: Gros Ventres, meaning “big bellies.” The tribe allied with the Blackfoot nation to add support to fight the United States government. The tribe would then go on to betray the Blackfoot by siding with the Crow people. This move proved disastrous.

Lummi Woman

In this shot, a Lummi woman with her traditional earrings stares at a distant point off-camera. Her nation the Lummi, was renowned for its maritime skills and its formal name, Lhaq’temish, which directly translates to “People of the Sea.” The tribe is known to have nomadically roamed the Washington area for close to twelve thousand years.

Trade relations with early Asian and European explorers remained sound for years until the United States government earmarked the Lummi land for mineral and supply exploitation. The Lummi of today reside in the same area and have revived most of their traditions.

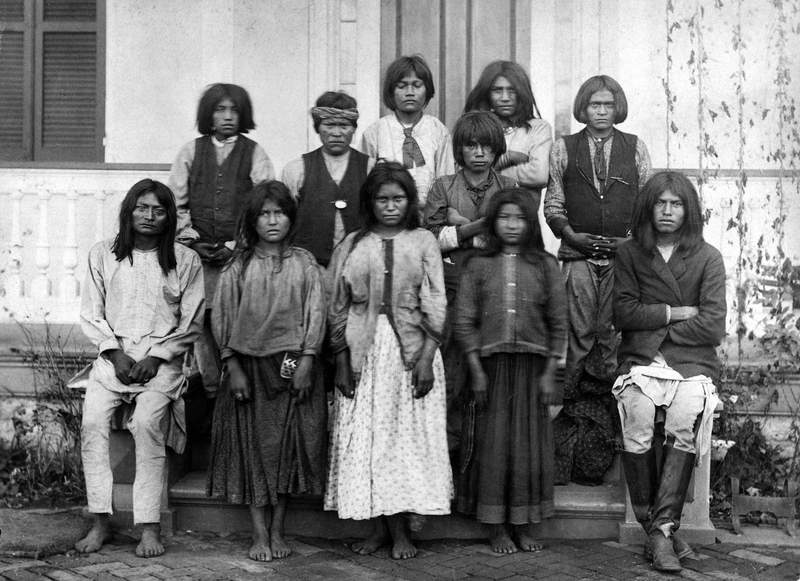

Chiricahua Carlisle

A bleak chapter of Native American history is captured in this photo of eleven children and teenagers before attending their first day of school at Carlisle Indian School in November 1886. The Carlisle Indian School was an attempt by the United States government to force the assimilation of Native American children into Western culture and appearance.

The Chiricahua people were known as nomads and part of the Apache people, were skilled warriors known for their resilience and had the reputation of being the most warlike of all the Arizona nations. The cold, snowy land of Pennsylvania, where the Carlisle school was located, was a far cry from their desert homelands.

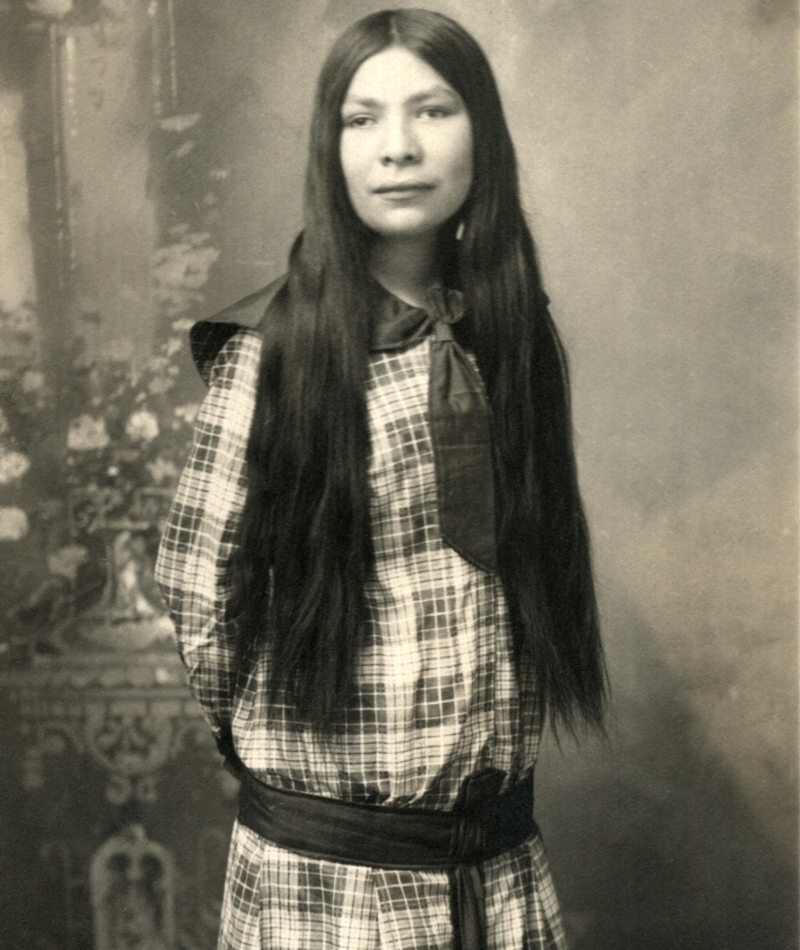

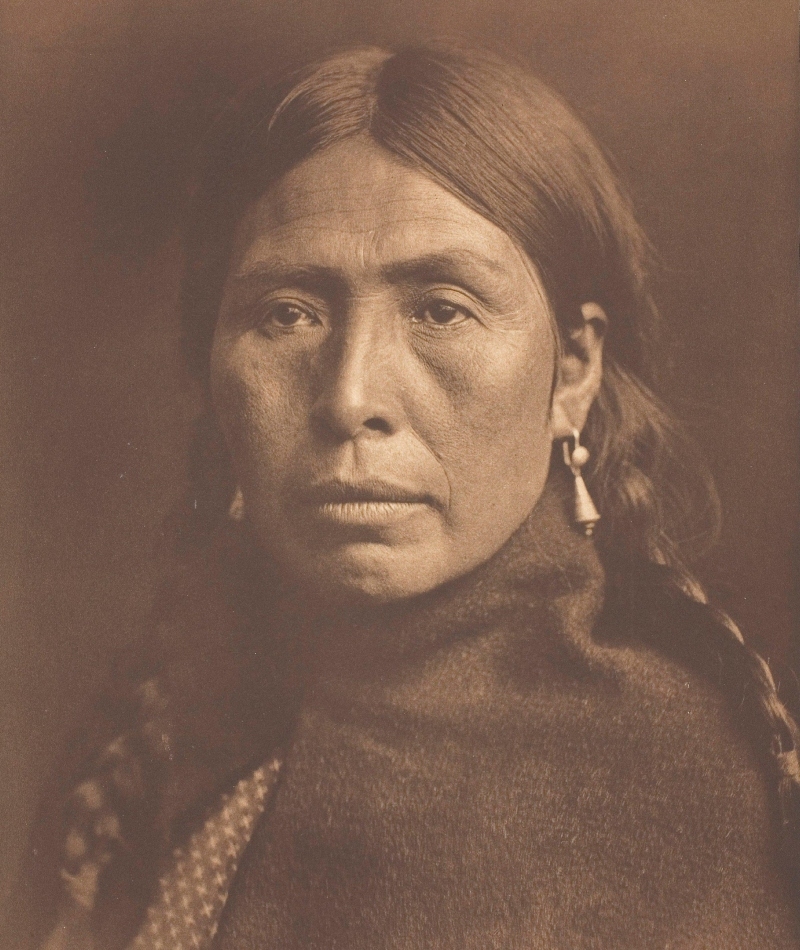

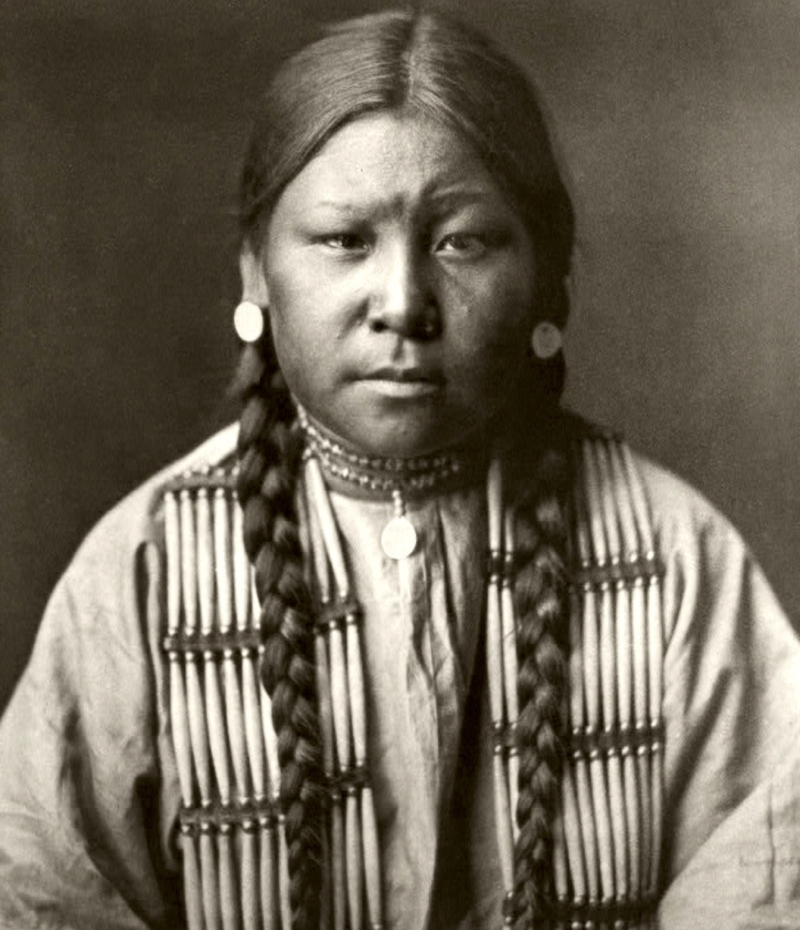

Cheyenne Woman

A young Cheyenne woman gazes intently into the camera lens. Her gaze became immortalized in the sixth volume of Edward Curtis’ seminal "The North American Indian" book series. The Cheyenne nation she belonged to was one of the most influential nations in Native American politics and history.

The Cheyenne's intricate trading and bartering system saw them amass a sizeable economy primarily based on goods produced from bison. Once the competing tribes and European settlers hunted the buffalo to near extinction, though, the Cheyenne lost their economic footing and had to rely on the United States government for financial assistance.

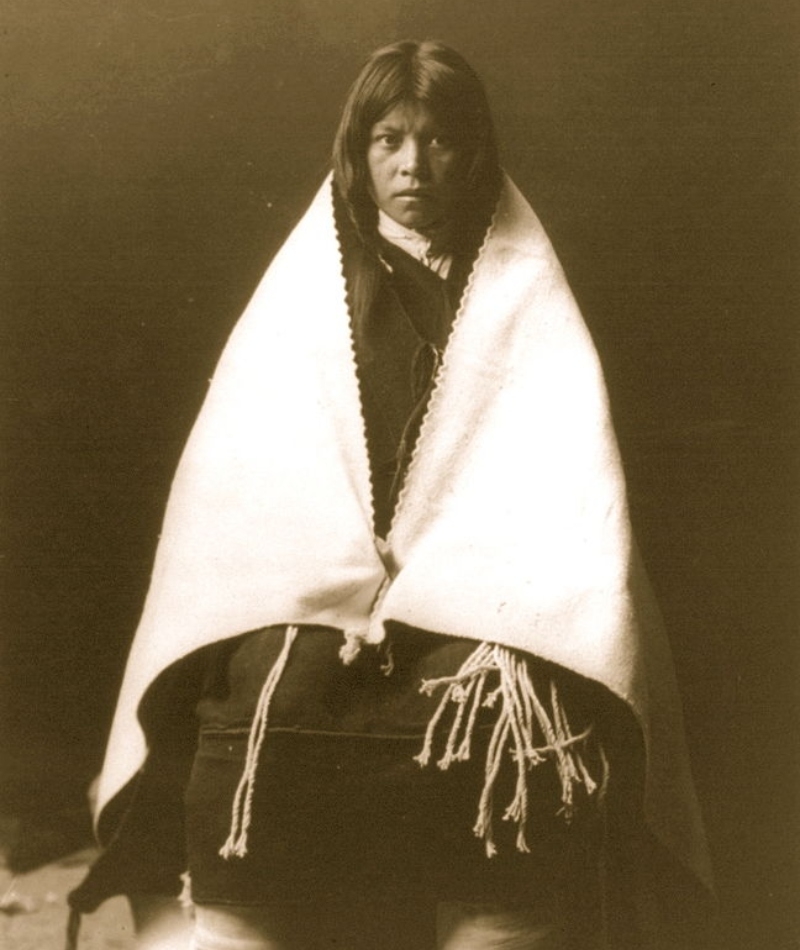

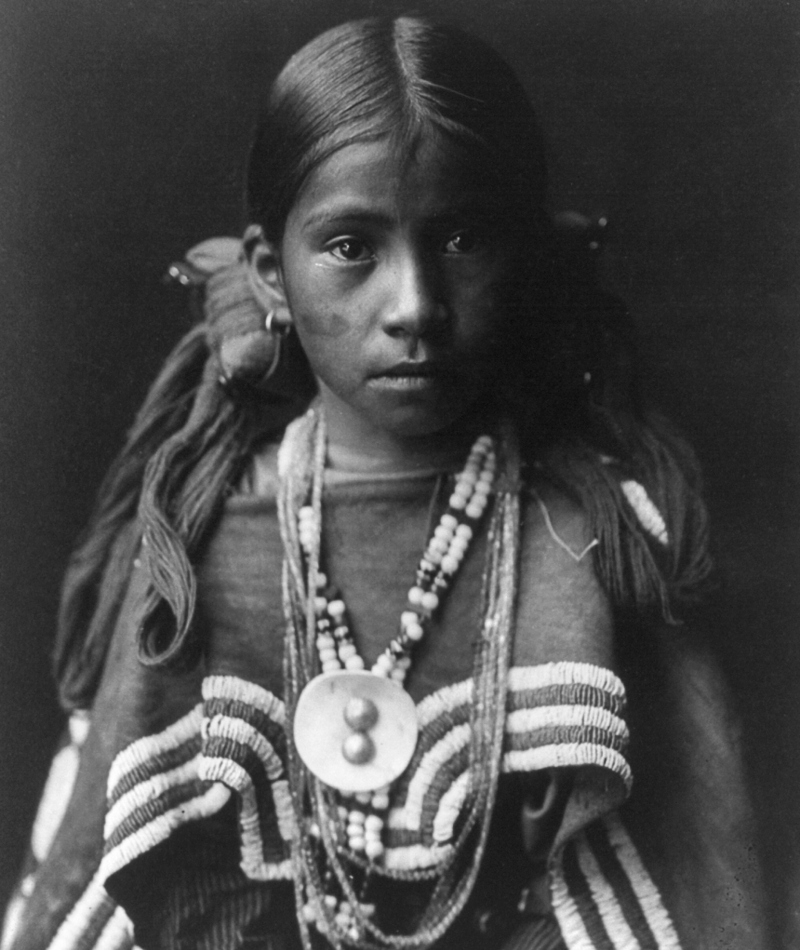

Jicarilla Girl

The wide-eyed Jicarilla girl in this image is dressed in her traditional “feast dress.” The feast dress is a particularly ornate garment that signifies a young Jicarilla woman’s entry into womanhood. The cape is decorated with lunar patterns symbolizing the phases of the moon and the feminine cycle.

The feast itself is a celebration that lasts up to four days, where the women of the community share experiences and lessons with the girl. The advent of domestic sewing machines in the late 19th century did little to change the tradition of the dress and elevated it to an even more unique status.

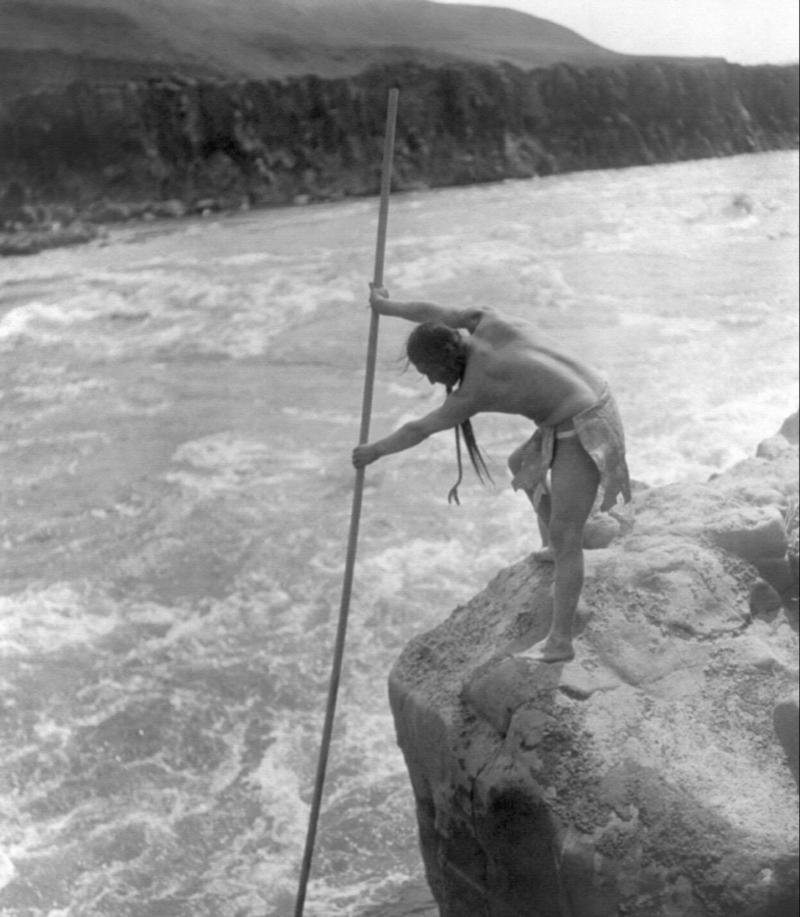

Wishram Salmon

The Wishram people, a tribe residing along the Columbia River, possessed a vibrant cultural heritage and are known for their intricate basketry, fishing expertise, and deep reverence for the natural world. The Wishram man spearing salmon in this image provides clear evidence of their closest environmental alliance: the river. The river primarily offered most of the Wishram diet, including sturgeon, eel, and salmon.

Situated in the center of crucial regional trade routes, the Wishram served as an essential trading strategist for the area. Their trading economy was mainly comprised of canoes, fish, blankets, and even enslaved people captured from neighboring tribes. Modern-day dam construction greatly impacted the ancestral lands of the Wishram and destroyed their independence.

Shows as He Goes

Shows, as He Goes (yes, this was his full name), was an eminent chief that fought in several running battles against the advancing United States government. By the time the photographer, historian, and ethnologist Edward S. Curtis took this image, Shows, as He Goes, had long been retired from the battlefront.

The famed “Indian Wars” were over, a new struggle for land independence was fought through courts, and legal counsel had begun. Shows as He Goes most likely belonged to the Crow nation, who were dominant in the northern parts of the United States around states such as Montana and North and South Dakota.

Haschebaad

The Navajo people have a diverse pantheon of gods and goddesses. The ritualistic mask worn by a Navajo man in this image is representative of the deity Haschebaad. The mask is worn during medicinal ceremonies as the goddess's power is believed to bless the sick. Only Navajo men are permitted to wear this mask.

Unlike masks representing masculine deities, the Haschebaad mask allows the men to display their hair further to emphasize the more feminine characteristics of the goddess. While not particularly ornate, the mask always has a piece of abalone shell and either turkey, woodpecker, or eagle feathers attached.

Acoma

In this next photo, we see this Acoma man staring serenely into the camera lens. The Acoma nation is indigenous to the southwestern parts of the United States, particularly around the state of modern-day New Mexico. The Acoma village, believed to have been founded in the 12th century, is a world heritage site that still retains most of its original structure.

The Acoma built the village atop sheer cliff faces to prevent marauding and attacks from nearby neighbors. The cliff faces provide a natural defense, and the only access to the village was via a narrow stairway chiseled out of the rock bed.

Zuni

Like many things in the Native American culture, things are often named after places in nature or animals. The Zuni people take their name after the river that sustained their ancestors in what is now modern-day New Mexico. The Zuni developed agricultural practices early in their settling on the North American continent and acquired a thriving local economy for hundreds of years.

A catastrophic drought forced the Zuni to move further south, which brought them into conflict with the Navajo and Apache nations, who did not take kindly to the newcomers. The Zuni eventually found sanctuary and lived in relative peace until Spanish colonists raided their cities in expectation of finding gold.

Kotzebue

Here is an interesting photo of a lone Inupiat hunter rowing through the reeds in search of muskrats. The photograph was taken in the Kotzebue region of modern-day Alaska, home to the Inupiat nation. The settlement is acknowledged as the oldest in all of the Americas and dates back as far as ten thousand years.

Although an incredibly remote outpost in the Alaskan wilderness, Kotzebue served as an important trade route for seafaring people long before Asian and European influence. The area grew in population and prominence after German explorers established a post office there. Today, almost 4000 people inhabit Kotzebue.

Papoose

The Apache people who were found mainly in the southwestern United States, are renowned for their warrior practices, profound spiritual bond with the land, and an enduring cultural legacy that has been preserved for generations. This photo shows a doting Apache mother holding her beaming child safely wrapped in their “papoose.” The word “papoose” originates from Algonquian and can be translated simply as “child.”

The term also evolved to encompass the very robust cradleboard that many Native American children found themselves wrapped in. The word has caused some controversy as it was used as a catch-all to describe Native American children. A Puritan minister compiled a book of Native American languages in the 17th century that injected “papoose” into everyday use.

Kutenai Embarking

The Kutenai people are a Native American tribe residing in the Pacific Northwest and the Rocky Mountains, known for their deep spiritual beliefs, hunting skills, and vibrant cultural traditions. In this photo, we can see two Kutenai people preparing to embark on an unknown mission in their canoe in this photo by Edward S. Curtis.

The river is a fitting setting for the photograph as the Kutenai were known as “Skalzi,” the lake and water people, by neighboring tribes. The Kutenai were paid tremendous respect by both their neighbors and the expanding colonists. Their society, although enslaving people, was considered progressive at the time as there were no extreme hierarchies or brutal punishments for crimes.

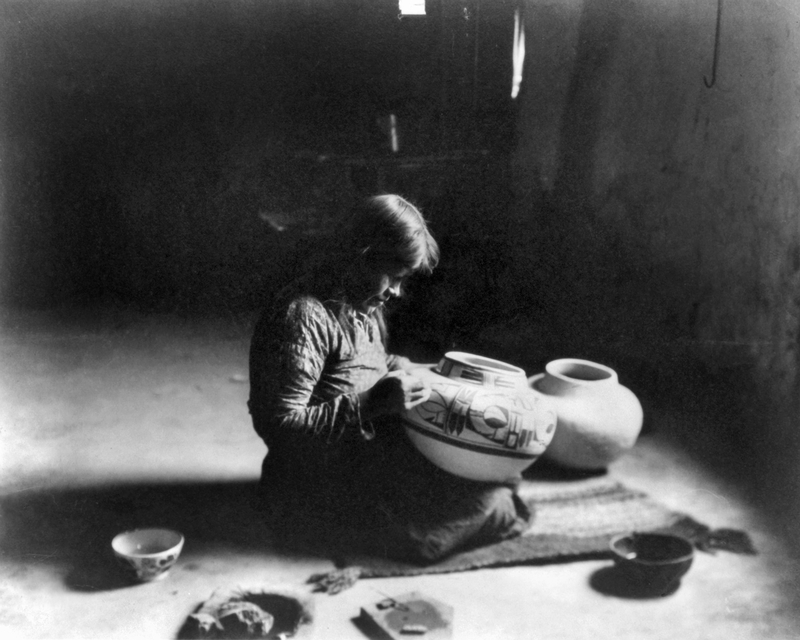

Nampeyo

Nampeyo was a renowned potter and artist from the Hopi Nation in southern Arizona. Her skills at recreating and innovating old Hopi styles became well-known, and she is credited with being the originator of contemporary Hopi artistic pottery. Nampeyo relied on all the traditional ways of pottering and painting, including using the yucca plant leaves as a brush.

Nampeyo’s prominence grew to such an extent that she and her husband traveled, by invitation, to an exhibition in Chicago to display her pottery and skills. Nampeyo was active between the 19th to early 20th centuries and is renowned for her intricate designs and exceptional craftsmanship.

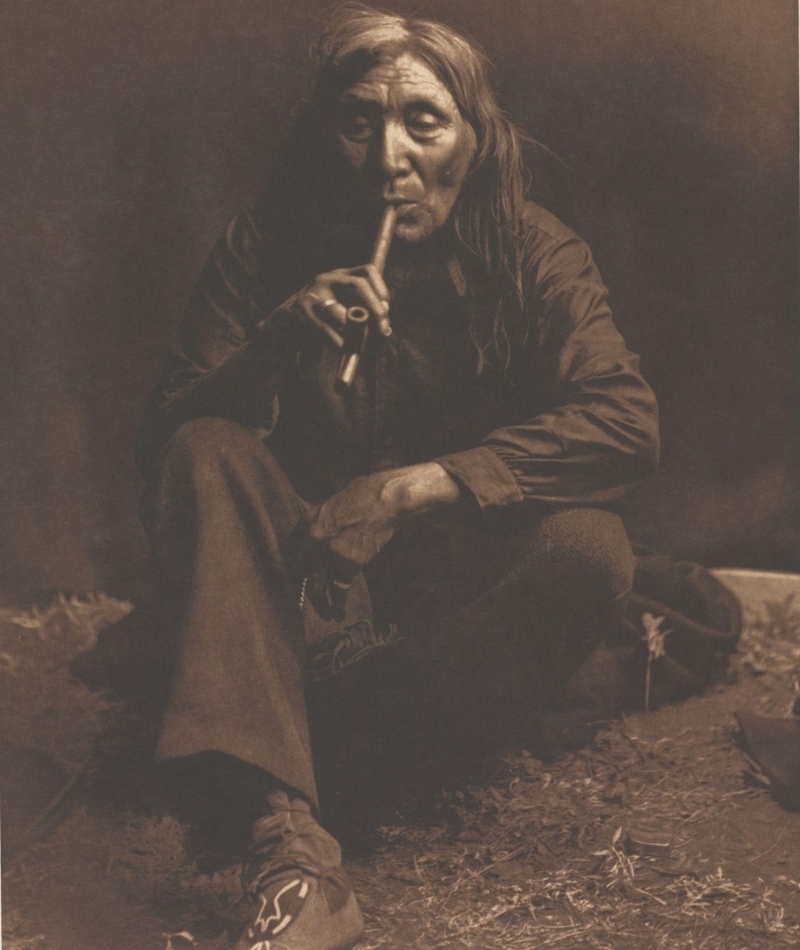

Piegan Blackfoot

The history behind this elderly man smoking his pipe in this image is unknown. What is known, however, is that he belonged to the Piegan tribe. The Piegan people made up the largest share of the three tribes that comprised the Blackfoot nation. The Piegans were originally agriculturalists until they migrated far enough south to begin buffalo hunting and are known until this day for their strong worrier culture.

This brought them into conflict with several other tribes, and the Blackfoot nation became known for its military might. The reign of the Piegans came to an end with a dismal buffalo hunt, and widespread starvation devastated the nation.

Princess Angeline

Chief Seattle had a peaceful and prosperous relationship with the early European settlers who made modern-day Oregon their home. His eldest daughter, Kikisoblu, found particular kinship with the townsfolk, and she was given the name “Princess Angeline” to make all aware of her regal status. Kikisoblu moved into the growing town of Seattle, which was named after her father, and lived a simple and unassuming life.

She had no care for politics and took up offering laundry services and selling hand-woven baskets to make a living for herself. She embodied resilience and cultural preservation throughout her life, inspiring generations with her strength and wisdom.

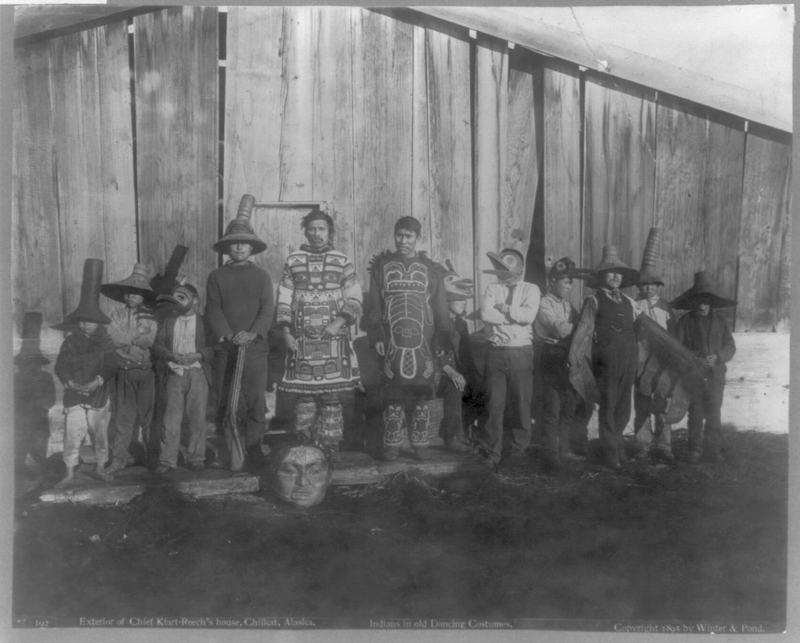

Tlingit

The Tlingit people had a reputation as true artisans and were renowned for their trading and commerce. As with many Native American tribes, the Tlingit were hunter-gatherers that did not settle in one location, and this brought them into contact with many other tribes, which, in turn, broadened their extensive bartering skills. Master weavers, jewelers, and artists, the Tlingit traded clothing and jewelry for canoes with their neighbors.

When Russian prospectors and the Tlingit people first encountered each other in the late 16th century, the exchange was amicable. The relations soon changed with disputes over trade routes that led to bloody conflict.

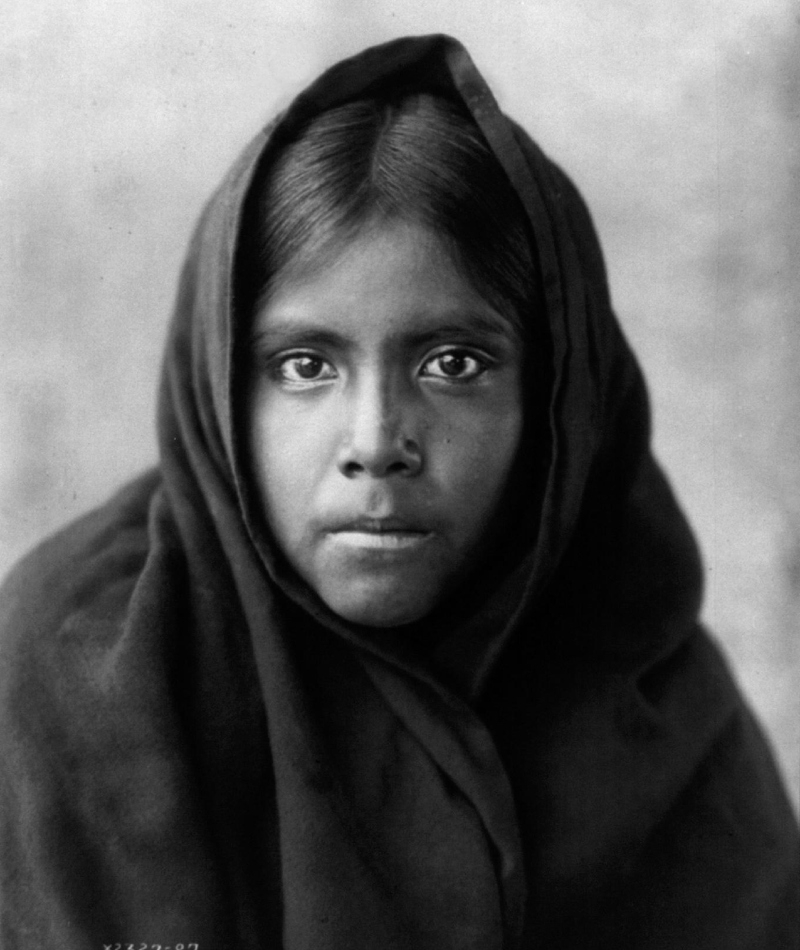

Qahatika Girl

The piercing eyes of a young Qahatika girl meet with the camera lens of noted ethnologist and historian Edward S. Curtis. It is understood that the Qahatika people, who are known for their rich cultural heritage and deep connection to the land, initially split off from their much larger ancestral group, the Pima, after being defeated in a battle with the Apache.

The Qahatika were not nomadic and developed a system of agriculture known as dry farming in the harsh Arizona landscape. Dry farming was the reliance on winter rains that could ensure a bountiful crop of wheat throughout the summer.