As with most nursery rhymes, there’s no corroborative evidence behind any of the theories of origin, just plenty of speculation. Some say that the rhyme is much more cut-and-dry, and others see a deeper meaning behind it and believe that it’s not just about wool.

More specifically, they think it’s about the very harsh (and high) taxation of wool in 13th century medieval England by King Edward I. Under the imposed tax, a third of the cost of just one sack of wool went to the king, while another went to the church, and finally, just one to the farmers themselves.

First Nursery Rhymes

Most of the popular nursery rhymes that we know first arose in the 17th century, though they have been around for much longer than that. The first known recorded nursery rhyme was actually a French poem that’s somewhat like "Thirty Days Hath September" and hails from the 13th century.

Nursery rhymes also started in books as marginalia (little notes in the book’s margins.) Then, in the 16th century, these types of short little rhymes started being used in English plays.

Tommy Thumb’s Song Book

The first collection of nursery rhymes was published in the form of "Tommy Thumb’s Song Book." The book came out in 1744 and was created by Mary Cooper.

A few decades later, the term “Mother Goose” was coined when Thomas Carnan published Mother Goose’s Melody in 1780. After that, they were used throughout the centuries as a language-learning tool for young children.

Nursery Rhymes and Development

Nursery rhymes can help with language development and acquisition in a number of ways, thanks to the rhymes and rhythms involved. And it isn't just English skills, but they help to develop, but also spatial reasoning, which can improve a child’s mathematical abilities.

Have we thought at all about the meaning behind the words of the nursery rhymes that are playing on repeat in children’s heads? Some of the dark origins of these supposedly innocent childhood nursery rhymes may shock you.

Goosey Goosey Gander

Like most nursery rhymes, "Goosey, Goosey Gander" sounds innocent enough because it’s programmed into your head from a young age and on.

However, as soon as you take a look at the words about throwing a man down the stairs for not saying his prayers, it becomes clear that it’s not really just your average childhood sing-along.

The Words

The earliest known version of this rhyme was published in London in 1784 in "Gammer Gurton's Garland or The Nursery Parnassus."

In this version, the last four lines, “there I met an old man who wouldn't say his prayers, so I took him by his left leg, and threw him down the stairs,” don’t exist. In fact, it’s much more innocent, with “there you’ll find a cup of sack, and a race of ginger,” after “in my lady’s chamber.”

Real World Origins

The updated version shines a light on some very real issues that have plagued the world since humans started spreading out throughout it. It is said that the rhyme refers to places in which Catholic priests would hide during a very protestant King Henry VIII’s reign. (As well as his descendants Edward and Queen Elizabeth.)

If the priest was discovered hiding in one of these “priest holes,” he would be forcibly removed from the home – even if it’s meant getting thrown down the stairs.

Little Bo Peep

Aside from it being a popular childhood rhyme, there’s nothing innocent or friendly about Little Bo Peep, not even at first glance.

The rhyme tells the tale of a shepherdess who loses her herd of sheep, dreading that something awful has happened to them. And what she finds at the end of the rhyme doesn’t just make her own heart bleed.

The Discovery

In what is perhaps one of the most famous nursery rhymes in the English language, a young girl falls asleep and wakes up only to find her sheep all missing.

She’s hopeful that they’ll come home soon, wagging their tails behind them. But one day, she goes wandering into a meadow and discovers their actual tails hanging up in a tree. Gee, what a wonderful image to plant in a child’s head!

Humble Beginnings

The earliest recorded version of the rhyme stems from 1805, though there are rumors that children used to play a game called bo-peep — a version of Hide and Seek — in the 16th century. The first time it was officially published was in 1810 in "Gammer Gurton's Garland or The Nursery Parnassus."

Some say it also may have something to do with a darker origin, as in the 14th century, the phrase “to play bo-peep” meant to hold someone in a pillory, which was a torture device used to humiliate and abuse.

London Bridge is Falling Down

Everyone who grew up in the English-speaking world knows this rhyme, which is also known as "My Fair Lady," or simply "London Bridge." It has catchy lyrics and a catchy tune now, and although no one is certain of its meanings, it is based on a dark past and some troubled times.

One theory is that it revolves around the bridge being majorly damaged in 1633 and again in 1666. But another explanation is much, much darker.

Human Sacrifice

Many speculate that the rhyme is referring to a process called immurement, which caused some poor souls to be entombed within the bridge during its reconstruction.

Some thought that, without a guard, the bridge would perish again, so they buried people within it so they could always look over it. There is no proof that these bodies exist, but there’s no proof they don’t, either.

The Viking Attacks

Another theory of the origin of this rhyme dates all the way back to 1014, in the times of Olaf II of Norway. The story goes that the king deliberately destroyed the bridge, though many historians believe it never happened.

Still, in a 19th-century Norse translation, it says, "London Bridge is broken down. — Gold is won, and bright renown. Shields resounding, War-horns sounding, Hild is shouting in the din! Arrows singing, Mail-coats ringing —Odin makes our Olaf win!"

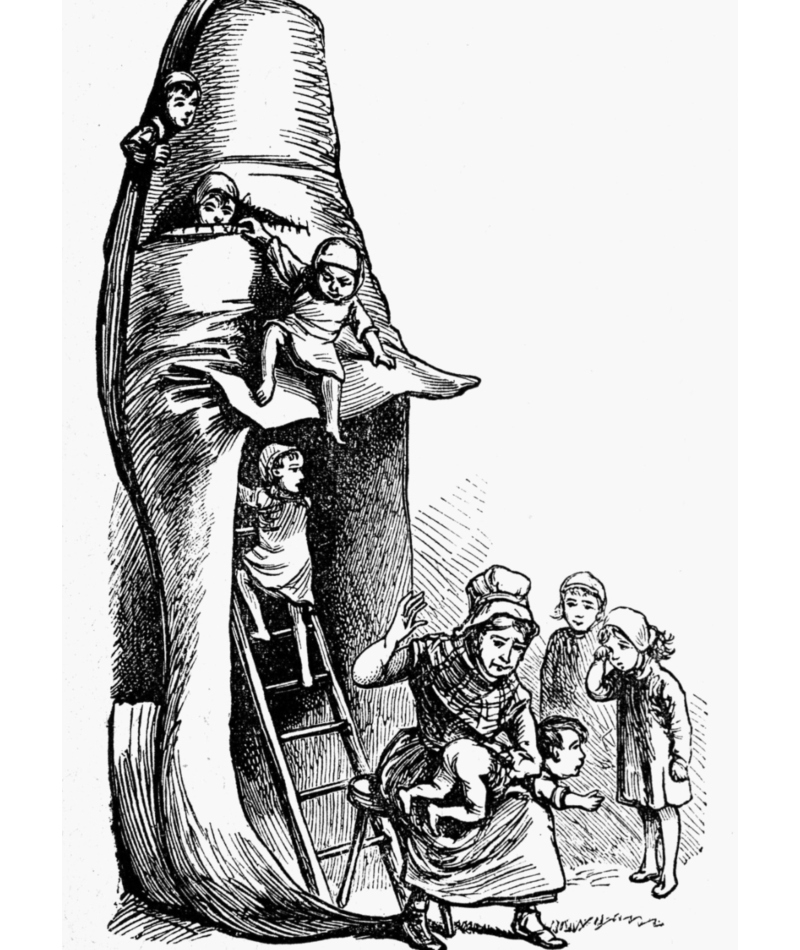

There Was an Old Woman Who Lived in a Shoe

While it may not seem so terrible right off the bat, there’s a lot to be said for this nursery rhyme, which seems to come off as an ad for antinatalism.

As if living in an old shoe isn’t bad enough, doing so while single-handedly trying to populate the planet has got to be exhausting. She has “so many children she doesn’t know what to do,” – and that included when it came time to feed the people she created.

Mother Goose

Written by the famous imaginary author, Mother Goose, the poem was first published in 1794 and explores the daily lives of a struggling family.

Some say that it alluded to the eight children of monarchs King George II and Queen Caroline, though they certainly had the means, if not will, to take care of their offspring. But then, what about control of Parliament?

The Basis

The rhyme has also been said to have been focusing on a number of famous figures throughout history, including Elizabeth Vergoose of Boston.

Vergoose had six biological and ten stepchildren. She is also speculated to be THE “Mother Goose,” if there ever were, in fact, such a person in history.

Three Blind Mice

Of all of the nursery rhymes in the English language, Three Blind Mice is among the most beloved. It pops up in popular culture all over the place; shows, songs, etc., and there’s no denying its dark nature. But has it always been that way?

The first known version of the rhyme was published in 1609 by Thomas Ravenscroft, and the words didn't seem so violent at that point.

Carving Knife

In the original version of the rhyme, the poor mice don’t end up getting their tails cut off by a woman with a carving knife. Some speculate that the woman in the poem who uses the carving knife is none other than the infamous Queen (Bloody) Mary.

Again, they believed it alluded to the harsh religious situation of the times. But was there indeed a hidden message within these words, or was it just a silly rhyme?

The Full Version

In the popular, modernized version of the rhyme, the poor mice wind up in the hands of a madwoman who cuts their tails off with a carving knife. However, in the full version, published in 1904, they wind up living happily ever after.

Not just that, but they actually learn some new skills along the way. The book is titled "The Complete Version of ye Three Blind Mice."

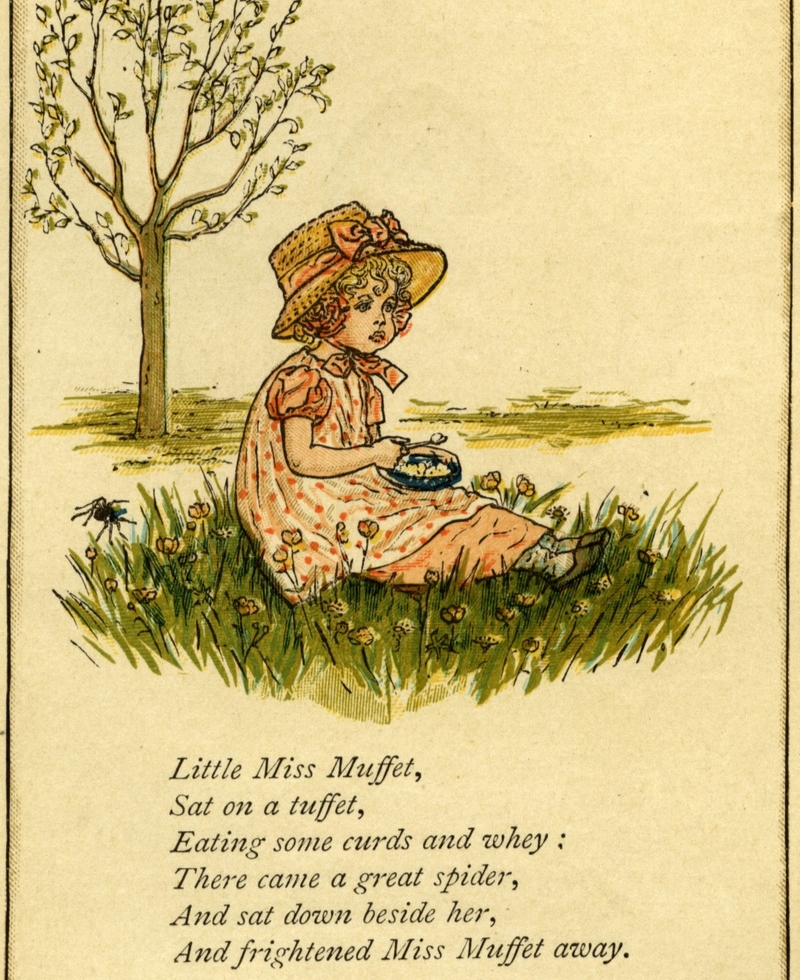

Little Miss Muffet

Little Miss Muffet is an excellent precursor to realizing how girls, women, and fully grown men handle seeing spiders in unexpected places.

The first recorded version of the rhyme dates back to the 19th century in England and was printed in an 1805 publication titled "Songs for the Nursery." It tells the tale and of a young woman who’s just trying to enjoy her cottage cheese outdoors on a nice day but gets startled by the sight of a spider.

The True Story

Interestingly enough, Little Miss Muffet is based on a real person: Patience, daughter of Dr. Thomas Muffet, who passed away in 1604.

Muffet was a physician and entomologist who authored a book about insects. And, of course, the rhyme has somehow also been rumored to be connected to Mary, Queen of Scots.

The Evolution

Those who believe the rhyme has something to do with Mary Queen of Scots think that the “spider” is, in fact, John Knox, infamous religious reformer. Plus, there was a pretty big gap between the publication of the poems and the death of Dr. Thomas Muffet.

The rhyme appears in a number of works today in different forms, including “Along Came a Spider” by James Patterson.

Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary

Now, this rhyme has a pretty good chance of being based on Bloody Mary — it even has her name in the title, twice. Of course, there are a few other theories about the origins of this popular nursery rhyme, most of which have some historical or religious significance.

The difference between this and the other ones previously on the list is that this one's darkness is a bit hidden rather than laid out on the surface to see.

The Origins

"Mary, Mary, quite contrary, how does your garden grow?" That is the first line of the most famous variation of the rhyme that floats around today. The original version isn't so different, simply beginning with “Mistress Mary” instead.

Many say the rhyme is a religious allegory of Catholicism, while others say the silver bells and cockle shells refer to Bloody Mary's torture devices. Yikes!

Bloody Mary

Let's say that the rhyme was referring to the infamous Bloody Mary and that the “garden” is the entire country. In that case, the silver bells then could have been quite literal.

The bells would then refer to a device that was used to crush a victim’s thumbs between two hard surfaces, while cockle shells were used...below the belt. We think we speak for everyone who feels things when we say — ouch!

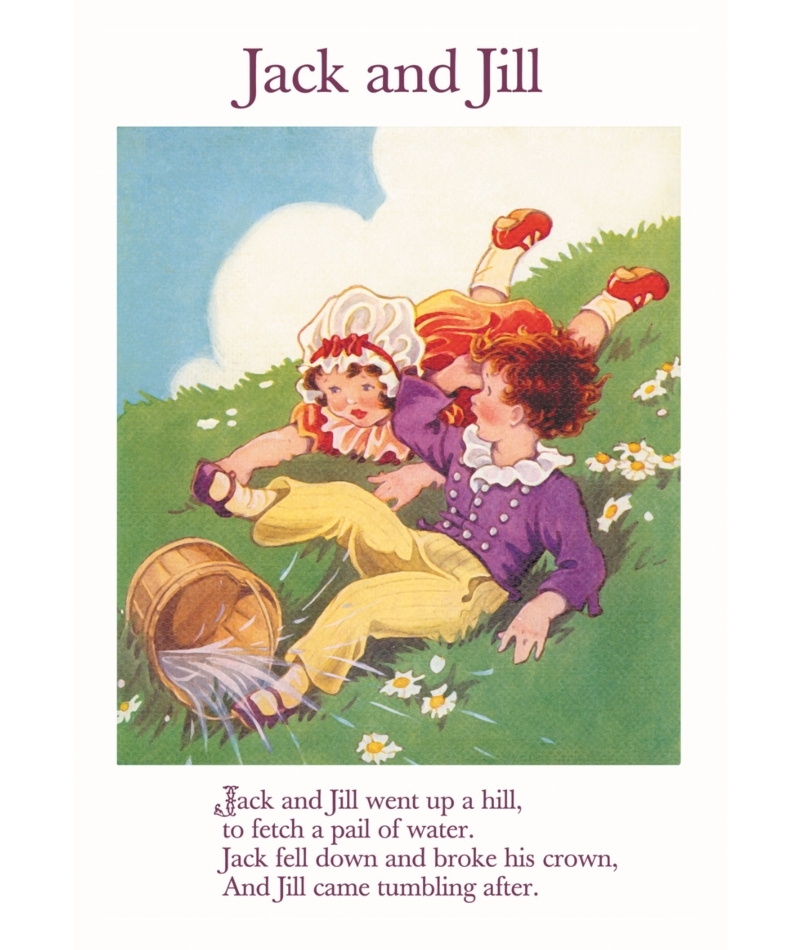

Jack and Jill

In the earliest version of this rhyme, Jill was spelled “Gill.” "Jack and Gill Went up the hill, to fetch a pail of water, Jack fell down and broke his crown, And Gill came tumbling after."

It's one of the most popular childhood nursery rhymes in the English language and dates back to the 17th century, though it’s gone through a few variations. But what does it all mean?

Basis

There are a few theories behind the origin of the rhyme, which includes a ploy by King Charles I of England to reduce the volume of a Jack (an eighth of a pint) while keeping the tax the same.

If this were the case, Gill would be a quarter pint of liquid that came “tumbling after.” Of course, there is no evidence that this is the definite origin; it’s just one of the theories.

Executions

Another theory that has a basis in history is that the rhyme refers to the 1510 executions of Edmund Dudley and Richard Empson. The two were killed for reasons of financial treason (or unpopularity, as some say) after King Henry VII’s death.

Then, some speculate that it has something to do with Thomas Wolsey’s 1514 marriage negotiation.

Rock-a-Bye Baby

In 1951, "The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes" identified "Rock-a-bye Baby" as the first English poem written on American soil.

Some theories speculate that the rhyme was written by a colonist who observed Native American women rocking babies sleep in cradles made of birch bark. The other theories, however, aren't so friendly.

King James and His baby

One origin story of the rhyme says that the Cradle is actually the Royal House of Stuart and tells the tale of King James VII’s son. Legend has it that he was switched with another baby at birth to provide a Roman Catholic heir for the king.

In this version, the wind refers to the Protestant force. As grim as this may sound, it's not even the darkest of the origin tales.

The Ritual

The last theory behind where Rock-a-bye Baby comes from a supposed grim seventeenth-century ritual.

To perform the practice, grieving mothers who’d lost newborns would put the child's body in a basket, hang it from a tree and let the wind rock it to see if they’d come back to life. Unfortunately, most of the time, the child's dead weight would break the branch.

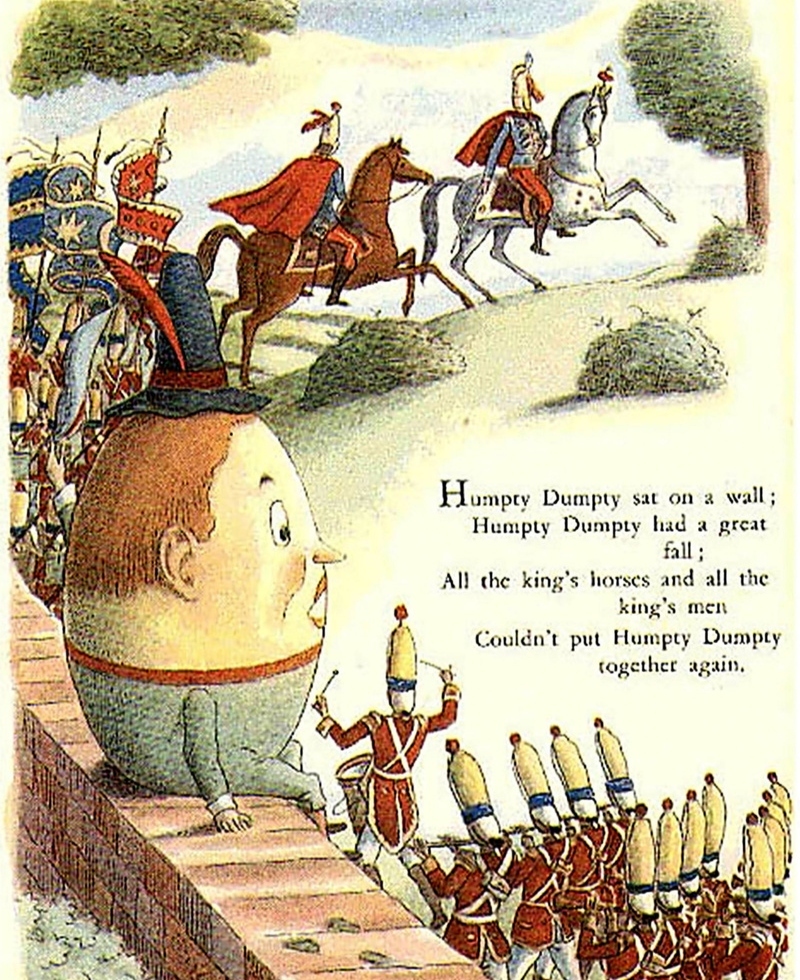

Humpty Dumpty

There’s no growing up in the English-speaking world without learning Humpty Dumpty’s rhyme. The rhyme, a tale about a giant egg, dates back to England somewhere in the 18th century.

The common text of the rhyme is particularly short compared to others on our list, which makes it more memorable. But what about the rhyme’s origins? The answer may vary, depending on where you look.

The Early Version

The earliest version of the rhyme, which was published in 1797, goes like this: "Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall, Humpty Dumpty had a great fall. Four-score Men and Four-score more, Could not make Humpty Dumpty where he was before."

The later versions aren’t so different. In fact, the two lines are exactly the same in the popular spin, which ends in “All the king's horses and all the king's men couldn't put Humpty together again.”

Tale or Ale?

There was also a drink called a Humpty Dumpty in the 17th century, which was made of brandy that was boiled with ale. It was also slang for a clumsy short person, in those times.

Some say the rhyme was originally created as a riddle, though no one is certain. There are many who believe it had something to do with a cannon that was a part of the English Civil War, as well, and there is a spoof version of the rhyme, written in 1956, based on that theory.

Little Jack Horner

"Little Jack Horner" is another famed English nursery rhyme that first popped up in the 18th century.

The rhyme, which comes along with a little tune like many others, goes like this: "Little Jack Horner, sat in the corner, eating his Christmas pie; He put in his thumb, and pulled out a plum, and said, "What a good boy am I!" So, where did this one originate from, exactly?

Bad Teacher

The first time the nursery rhyme was ever documented was in "Mother Goose’s Melody," published in 1765. However, the 1st surviving version was published in English in 1791. Unlike many others in our article, this poem actually has a cheery disposition.

In fact, the story behind it is actually quite inspiring — at least one of them is. As one story goes, the rhyme is based on Thomas Horner, a schoolboy who gets sent to the corner by his teacher for rejecting a racist lesson. However, there are a few alternate theories behind the tune.

Bringing Politics Into It

The first known version of the rhyme, published in 1725, called Namby-Pamby, was written by Henry Carey and said to be a political satire. The target? Prime Minister Robert Walpole.

After that, a political theme started to develop, and other related poems and rhymes along with it. Samuel Bishop, for instance, wrote: “What are they but JACK HORNERS, who snug in their corners, cut the public pie freely? Till each with his thumb has squeezed out a plum, then he cries, ‘What a Great Man am I!’”

Ring Around the Rosie

"Ring Around the Rosie," AKA "Ring a Ring o'Roses," Is one of the most popular nursery rhymes, along with playground games, for children. In the modern version, particularly the one that's popular in the United States, the ending includes the line “ashes, ashes, we all fall down,” which sounds a bit ominous.

In the original English version, however, it sounds more as if the characters have developed a cold than kicked the bucket. It ends with, “a-tishoo, a-tishoo, we all fall down,” instead.

Sinister Beginnings

There are many who believe that the origins of "Ring Around the Rosie" stem from the bubonic plague or the “Black Death.” That's the reason for the lines about tissues and falling down.

In the colonial versions of the rhyme, the “ashes” part is actually about cremating the bodies of those who’ve died. More modern versions of the rhyme have stemmed from this theory, including one that was born from the bombing of Hiroshima in the 1940s.

Counterarguments

Although the Great Plague origin story may seem to make a lot of sense, considering the words to the rhyme, there are those who disagree.

Some say that that explanation didn't even pop up until the middle of the 20th century, for one thing. Others argue that “fall” in the rhyme wasn't literal, but rather, referring to a type of curtsy or bow.

Baa Baa Black Sheep

Baa Baa Black Sheep is a popular nursery rhyme that dates back to 1744 and is sung along to the musical tune of a 1961 French song. The melody, "Ah! vous dirai-je, maman" (Oh! Shall I tell you, Mama), is used for many children’s learning songs, including "Twinkle Twinkle Little Star" and the alphabet song.

The combination of the words and tune of this particular song was first published in a book titled "Nursery Songs and Games in Philly", circa 1879.

The History

Unlike some of the other nursery rhymes, the words of this one have pretty much remained the same through the ages: “Baa, baa, black sheep, have you any wool? Yes, sir, yes, sir, three bags full; One for the master, and one for the dame, and one for the little boy who lives down the lane.”

It all sounds innocent enough, if we're talking about sheep, right? However, there are many who believe that this rhyme has dark origins, rooted in racism. If you look at it that way, it certainly becomes problematic.

Alternative Theories

As with most nursery rhymes, there's no corroborative evidence behind any of the theories of origin, just plenty of speculation. Some say that the rhyme is much more cut-and-dry, and others see a deeper meaning behind it and believe that it's not just about wool.

More specifically, they think it's about the very harsh (and high) taxation of wool in 13th century medieval England by King Edward I. Under the imposed tax, a third of the cost of just one sack of wool went to the king, while another went to the church, and finally, just one to the farmers themselves.

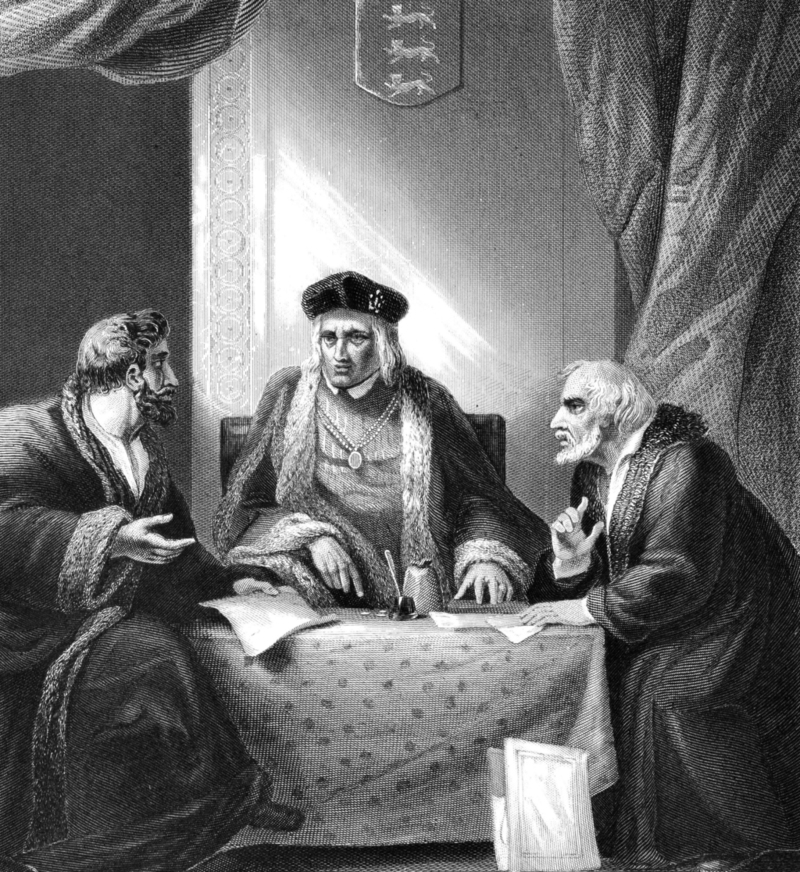

Old Mother Hubbard

We all know the rhyme about Old Mother Hubbard, who went to her cupboard to get her dog a bone, but the cabinets were bare when she got there, so the puppy had to do without.

This seems a lot cleaner than many of the other rhymes in our article that talk about things that get cut off or other types of violence. After all, the woman can just go to the store and get her dog another bone, right? But some say that Old Mother Hubbard isn't actually a woman at all. So, then what does it all mean?

The Heirless King

There are many who believe that Old Mother Hubbard is actually supposed to represent Lord Chancellor Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, who served under King Henry VIII.

Wolsey was attempting to get special permission to help the king, who, after 15 years of marriage to Catherine of Aragon, was still upset he had no heir to his throne. The king sought a divorce so that he could try with someone else. But unfortunately for them, the church was having none of it, and Wolsey failed, ended up losing all of his power, and dying in prison because of it all.

The Lengthier Version

The theory about the rhyme alluding to the king’s loss of his petition for divorce may make sense when dissecting the shortened version. However, there is a much lengthier version of the rhyme which could make one think twice.

In it, Old Mother Hubbard really does go to the store to get her dog something to eat, but when she returns, the dog is dead. But then, she goes to get him a coffin and comes back to find him laughing and alive. It is still very possible that the cupboard in the shortened version represents the Catholic Church, and the doggie, King Henry VIII.

Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush

The mulberry bush, or the mulberry tree, is actually a real thing. In fact, there are plenty of species of plants that use the name. But does this popular childhood nursery rhyme actually have anything to do with plants?

The rhyme was first recorded in the 19th century by a man named James Orchard Halliwell. Still, there are a few different theories behind the origin of the rhyme and children's game that's often played along with it. The game is designed to teach a young child to mimic certain actions, like stretching, catching, or kicking a ball.

The Rhyme’s Origins

One local historian, R.S. Duncan, also the warden at Her Majesty's Prison in Wakefield, believes the rhyme actually originated with prisoners at the facility. The inmates took a sprig from a golf club and planted it in the yard. Once it grew, they exercised around it for a period of time every day.

These days, the prison exclusively housed male inmates, though, at the time, it was the females who supposedly planted the tree. Others yet believe that the rhyme is a joke about the issues with the silk production industry in Britain in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Georgie Porgie Pudding and Pie

"Georgie Porgie Pudding and Pie" was first recorded in 1841 with the lyrics “Georgie Porgie, pudding and pie, kissed the girls and made them cry, when the boys came out to play, Georgie Porgie ran away.”

James Orchard Halliwell published a version of the poem in his book as well, with a spin on the lyrics, including the name Rowley Powley, and using a more specific type of pie — pumpkin, to be exact. Over the years, the rhyme evolved from a jingle to a taunt used on playgrounds everywhere. But that doesn’t necessarily mean it started out on negative grounds.

Bad Intentions

Whatever the true meaning behind the words of this rhyme is (which no one can ever be absolutely certain) there’s no denying it evolved into a taunt used by children everywhere. Kids have used the verse to try and shame larger children, and also anyone who may have a different sexuality than themselves.

The origins of the words are said to refer to George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham and an English courtier. He was said to be one of King James I’s lovers, though of course, there was never any type of proof of the supposed relationship between the two men.